You'd like to find out more about the range of services offered by the msg group? Then visit the websites of msg and its group companies.

Turkey in the contradiction between money laundering prevention and asset peace. But Turkey is not alone. Russia, too, is no stranger to this.

Turkey: a country between Orient and Occident, a country full of contrasts. Not only is it geographically partly in Europe, but also the motto of the founding father of this republic was: Always look to the West and not to the East. For decades, Turkey was considered pioneering and progressive for Muslim countries. Its longstanding aspiration to belong to the European Community has been reflected in its laws according to European standards. It has become a respected member of the international community, is a member of NATO as well as the OECD, and there has been a customs agreement between it and the European Union since 1995.

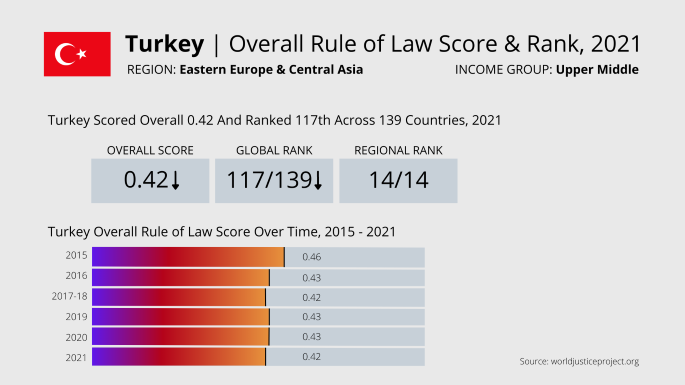

As a country between tradition and modernity, Turkey has been exposed to a wide variety of political currents. However, various developments over the last few years have led to a massive economic crisis and a decline in the rule of law. Turkey is now ranked 117th out of 139 countries worldwide in terms of the rule of law in the current list of the World Justice Project[1] (WJP). In the region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, it has even fallen to last place.

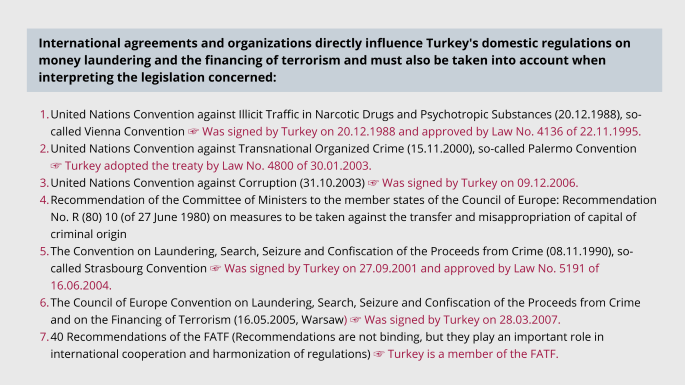

This divergence between European standards in existing legislation and conditions that lack the rule of law is also reflected in Turkey's anti-money laundering provisions. As a long-standing member of the FATF, Turkey has signed all major international agreements in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing.

The signed conventions have been incorporated into Turkey's national legislation. In 1996, a money laundering law was introduced in Turkey. In 2006, it was reformed to meet the international standards of the FATF.

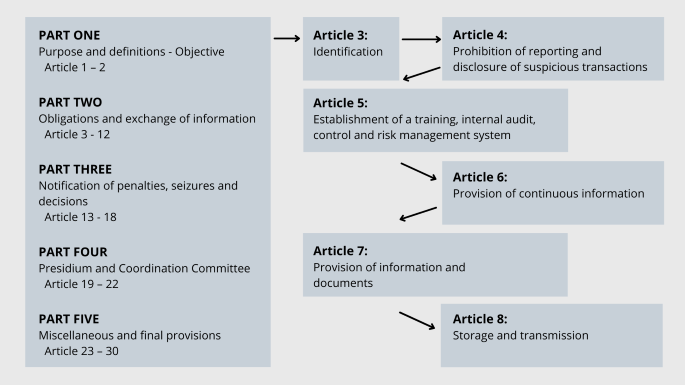

An overview of the Turkish Money Laundering Act (MLA) shows the similarities with the German money laundering regulation in its structure.

If we look at the obligated parties under the MLA, it is also apparent here that they are essentially no different from the group of obligated parties under the German MLA.

Obligated parties under the Turkish Money Laundering Law (Kanun 5549):

- Banks

- Insurance companies

- Private pensions providers

- Capital markets, credit and other financial services

- Post and transport

- Gambling and betting activities

- Foreign exchange, real estate, precious stones and metals, jewelry, transport vehicles, construction machinery

- Those engaged in the trade of historical artifacts, works of art and antiques or brokering these activities

- Notaries, lawyers

- Sports clubs and other areas designated by the Council of Ministers

Despite the existing laws, their application in practice gives rise to criticism.

The main criticism was that the country's supervision did not take sufficient action against high-risk sectors such as banks, gold and gemstone dealers and real estate agents. It is feared that terrorist groups, among others, are feeding their illegally acquired funds into the Turkish real estate market and integrate them from there into other sectors. Due to the geographical proximity to Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon and the relatively permeable borders to Turkey, there is also the concern that terrorist financing does not stop at the gates of Europe.[2]

Furthermore, in October 2021, the FATF reacted to the continuing crackdown on the civilian population with the grey listing. The specific criticism was directed against Turkey's "Anti-Terror Law" to "prevent the proliferation of the financing of weapons of mass destruction". Contrary to its title, this law does not contain any punitive measures or control mechanisms against money laundering or the financing of weapons of mass destruction for terrorist purposes. Instead, it authorizes the president to freeze the funds and assets of terror suspects.[3]

Ultimately, Turkey's treatment of non-profit organizations was also the focus of the FATF's criticism. The mere existence of criminal investigations on terrorism charges against a board member of initiatives, associations and foundations entitles the Ministry of the Interior and the government-appointed governors to suspend the persons concerned, paralyze the activity of the respective association and appoint a receiver in its place.[4]

This led to Turkey being placed on the grey list by the FATF in 2021. For example, it was found to have deficiencies in the implementation and enforcement of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing laws.[5]

Already in 2019, the FATF's Mutual Evaluation Report analyzed Turkey's anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures and identified a number of shortcomings. As a result, seven priority measures were called for. These include, for example, developing strategies for the confiscation of proceeds and instrumentalities and filling gaps in the legal framework in order to fully comply with obligations regarding targeted financial sanctions related to terrorism. There was also a call for the development of a Turkish national strategy for the investigation and prosecution of various types of crimes related to money laundering.[6]

The FATF addressed the supposed improvements in its follow-up process. In this process, the implementation of the FATF recommendations that had been criticized was addressed and a classification was made as to whether the criticized points had been remedied or at least partially remedied in the meantime.[7]

„Asset Peace“

One aspect that was not mentioned in any of the justifications submitted by the FATF is the so-called "asset peace". This Turkish law "Varlık Barışı", which translates as Asset Peace Law, has existed since 2008. This law was initiated to declare money, gold, foreign currencies and other capital market instruments from abroad and bring them into Turkey.

The content of this law aims to bring unregistered assets from abroad into Turkey without asking about the origin of the money brought into the country and without having a tax audit carried out in order to maintain the "asset peace". Assets brought into Turkey under the asset peace are not taxed. This law has been in place for 14 years now, and is renewed every six months. The last time it was extended for another six months was on New Year's Eve on December 31, 2021.

Residents also benefit from this scheme. Taxpayers who own money, gold, foreign currencies, securities and other capital market instruments as well as real estate that are located in the country but not included in the statutory general ledger records can declare them to the tax authorities and legalize them through the asset peace. Eligible persons are individuals and legal entities. The only condition is that the declared assets are brought into Turkey or transferred to an account to be opened with banks or brokers in Turkey within three months of the date of notification. Turkish citizenship is not required to benefit from the asset peace. The cash brought into the country is sufficient for a customs document.

The official rationale is that those with unregistered savings at home and abroad can now make their money official without fear of prosecution by the tax authorities. Retired auditor general and author Kadir Sev pointed out that implementing "asset peace" is one of the easiest ways to launder assets.[8]

The law is an amnesty scheme according to which it is irrelevant from which sources the assets originate. But it is precisely the examination of the origin of funds that is the basis of the fight against money laundering. It is a contradictory approach to combating money laundering if, on the one hand, asset peace means that there are no checks on where the money or assets actually originate. On the other hand, there are regulations in the Money Laundering Act that correspond to the international standards of the FATF.

The money enters the country via banks, brokers and intermediaries. This begs the question how such an arrangement can be reconciled with a bank's AML provisions. Is it black money, bribe money or are these funds used to finance terrorism? These aspects are not taken into account, so that, by law, banks are not supposed to analyze these aspects at all and reporting to the Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK) is not required. This counteracts MASAK's very own task of combating money laundering.

Consequences

Assets that - for whatever reason - were previously exempted from state control can become legal and registered assets through the asset peace incentive, without the source of these assets being questioned and those affected being subjected to a tax audit.

How can money laundering and terrorist financing be combated if the origin of the money is not questioned? Against the background of the country's geographical location, these circumstances hold enormous potential for laundering drug money and money from human trafficking in Turkey. Tax evasion is also legalized by this scheme. The tax amnesty removes the deterrent function and decreases the willingness to pay taxes voluntarily. The decline of the Turkish lira is driving more and more people into poverty. The impact of tax evasion, money laundering and corruption, according to a report by the UN body for transparency and accountability, is that resources needed to fight poverty caused by tax evasion, corruption and financial crime are exhausted.[9]

Against the background of such a law, it seems more than questionable that asset peace is not mentioned in the deficiencies in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing criticized by the FATF. Even if the criticized circumstances that led to Turkey being placed on the grey list were all remedied, the question arises as to how a scheme such as asset peace can be brought into line with a FATF membership that is committed to combating money laundering and terrorist financing.

At the same time, asset peace represents a major risk factor with regard to money laundering. This raises the question of whether the FATF actually did not notice this scheme or whether it was deliberately left out.

While granting some legitimacy to tax amnesties by invoking supposed benefits in terms of addressing economic challenges, it must not be the case that illicit assets are legitimized under the guise of asset peace.

Ultimately, Turkey will have to decide sooner or later whether it wants to continue on this path or credibly be a fellow combatant of the international community in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing.

Capital amnesty also in Russia

Russia is currently under economic pressure due to the sanctions imposed as a result of the invasion of Ukraine. The Russian rouble, like the Turkish lira, is plummeting. For these reasons, a so-called "capital amnesty" was enacted in Russia. This means that money taken abroad beyond the reach of the tax authorities can return to Russia without the threat of penalties or taxes.[10] However, this is nothing new in Russia. The Russian government has already passed amnesty laws in the past. As with asset peace, the purpose was to repatriate financial resources located abroad. This offer was intended to provide the Russian economy with urgently needed liquid funds. In return, this was made possible without subsequent payment of taxes.[11]

Even more intensively than in the first amnesty attempt in 2015, Russians are being offered to close the companies they control abroad and bringing back the money without having to pay tax on it afterwards.[12]

History of capital amnesty in Russia

Russia had introduced an amnesty for past tax and foreign exchange offences in 2014, when the country was struggling with massive capital outflows, low oil prices and sanctions from the West over the Ukraine dispute.[13] This first amnesty scheme was in place from 2015 to 2016, providing exemption from liability for tax and criminal offences, as well as regulatory offences related to declared assets. The amnesty had rarely been used and expired in mid-2016.

The second stage of the amnesty scheme was implemented from March 1, 2018 to February 28, 2019 and covered activities carried out before January 1, 2018. Due to the low take-up of the first amnesty scheme, new laws on the second stage of the amnesty were passed before the new presidential term:

- Federal Law No. 33-FZ “On Amendments to the Federal Law "On Voluntary Declaration of Assets and Accounts in Banks by Individuals” and “On Amendments to Individual Legal Acts of the Russian Federation" of 19.02.2018

- Federal Law No. 34-FZ “On Amendments to the First and Second Parts of the RF Social Code...” of 19.02.2018

- Federal Law No. 35-FZ “On Amendments to Article 76-1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation”[14]

For example, changes were made such as the abolition of the 13 per cent tax on retrieved funds. The tax exemption extended to funds in accounts at foreign banks and to foreign accounts that were closed before January 1, 2018.[15] However, the essence of the amnesty scheme remained untouched. Those claiming the amnesty were required to submit a special declaration to the Russian tax authorities, thus disclosing information about their assets and bank accounts abroad, as well as their shareholdings in foreign companies (including controlled companies). The amnesty covered violations of both foreign exchange and tax laws contained in the Criminal Code (Art. 193, 194, 198, 199, 199.1, 199.2), Administrative Offences Code (Art. 15.1-15.6, 15.8, 15.11, 15.25) and Tax Code of the Russian Federation.[16]

The third stage of the amnesty scheme was to last until March 1, 2020. The targets of the amnesty were now investors and businessmen who are willing to transfer their funds to Russian accounts and move their foreign assets to the special administrative areas in the Kaliningrad and Primorye regions.[17] Individuals can benefit from this, provided they move their funds from foreign to Russian accounts as well as re-register their foreign assets in the Russian offshore zones.

Commonalities and legitimacy

As with asset peace in Turkey, the Russian "capital amnesty" does not require disclosure of the source or origin of the money. In both countries, it is not only their own nationals who can take advantage of these schemes. The measures apply to Russian nationals and foreigners with a settlement permit. Like Turkey, Russia is a member of the FATF. In June 2013, Russia joined the FATF, committing to adhere to the FATF guidelines and benchmarks in its legislation. Here, too, the amnesty schemes cannot be reconciled with the essence of the FATF, the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing.

The capital amnesty laws in both Russia and Turkey aim to generate capital flows into the country in order to be liquid again. The examples of Russia and Turkey demonstrate that autocrats introduce measures to cushion themselves in the face of economic difficulties - even if this opens the door to money laundering and violates their obligations under their FATF membership.

[1] The World Justice Project (WJP) is an independent, multidisciplinary organization whose aim is to document the development of the rule of law around the world, to outline developments and to promote the rule of law worldwide.

[2] See blog post: What are the consequences of Turkey's inclusion on the FATF grey list?

[3] See blog post: What are the consequences of Turkey's inclusion on the FATF grey list?

[4] See blog post: What are the consequences of Turkey's inclusion on the FATF grey list?

[5] See blog post: What are the consequences of Turkey's inclusion on the FATF grey list?

[6] FAFT, Anti-money laundering und counter-terrorist financing measures - Mutual Evaluation Report 2019, Page 10 Priority Actions

[7] FAFT, Anti-money laundering und counter-terrorist financing measures – 1st Enhances Follow-up Report & Technical Compliance Re-Rating

[8] www.haber.sol.org.tr/haber/kara-para-aklamanin-en-kolay-yolu-erdoganin-varlik-barisi-aski-308261

[9] www.giz.de/en/downloads/170330_factsheet_BMZ_Steuer.pdf

[10] www.puls24.at/news/politik/russland-droht-westen-mit-harten-strafmassnahmen/258923

[11] www. ostexperte.de/oligarchen-ziehen-geld-aus-europa-ab/

[12] www.diepresse.com/5374305/wie-die-russischen-oligarchen-geld-aus-europa-abziehen

[13] www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/russland-putin-will-devisen-zurueckholen/20790790.html

[14] www.roedl.net/fileadmin/user_upload/Roedl_Russia/Newsletter/deutsch/Newsletter-Mai-Juni-2018.pdf

[15] www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/russland-putin-will-devisen-zurueckholen/20790790.html

[16] www.lex-temperi.de/aktuelles/news-anleger-und-geschäftsleute-profitieren-von-der-russischen-kapitalamnestie

[17] www.lex-temperi.de/aktuelles/news-anleger-und-geschäftsleute-profitieren-von-der-russischen-kapitalamnestie

What is not green is made green

The advancing social and political paradigm shift is reflected in the growing interest of investors and consumers in sustainability, environmental protection aspects and social responsibility. ESG (Environmental Social Governance) is on everyone's lips and refers to corporate orientation towards criteria of environmental protection and social responsibility as well as honest corporate governance beyond the legal minimum. The individual aspects of ESG are briefly explained below:

Environmental (E)[i] − climate and environment friendly: Green assets are booming, sustainable funds have more than doubled their inflows globally since 2019, from USD 285 billion in 2019 to USD 649 billion in 2021[i]. ESG funds currently account for around 10 per cent of the total market. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA)[ii] report, USD 35.5 trillion was in sustainable investments, according to Bloomberg Intelligence even USD 35.9 trillion – with a strong tendency to rise to an estimated USD 53 trillion[iii] by 2025. Society, the market, and regulators are key drivers of far-reaching ESG campaigns worldwide.

„It’s so green“ – also in reality?

Shares of the world's largest oil and gas giants such as Saudi Aramco, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, Total, Chevron, Gazprom or OMV are all represented in so-called “sustainable funds”, along with coal giants and mining operators such as Rio Tinto, Vale or BHP – despite their alleged responsibility for numerous environmental disasters and no less criticism from human rights organisations. No company or industry is excluded per se from the “sustainable circle” here, but often tolerated according to the best-in-class principle. For example, the top “green” quartile of companies in the underlying index is inevitably reflected as “green” in the ESG-listed funds. For this, it is sufficient if a company produces few CO2 emissions in comparison to others. It remains questionable to what extent sustainability and resource conservation are taken into account in the business model in absolute terms. The evaluation in relation to other index companies and a high tolerance threshold for undesirable sectors (up to 35%) are striking weaknesses for a comprehensive realistic sustainability rating. IT and digital service providers also not infrequently boast of being particularly energy-efficient and thus environmentally friendly by advertising increased computing capacity per second (FLOPS[iv] rate), but ultimately causing more overall consumption. This rebound effect is detrimental to nature, as only the absolute consumption figure would be crucial for it. In addition to the electricity consumption, the enormous water consumption for the cooling of server centres does not contribute to the sustainability of the IT multis either. Microsoft, for instance, shines with an AAA rating (source MSCI) with reference to its low CO2 emissions and its positive contribution to the maximum 2-degree Celsius climate warming target.

The EU and EBA[v] also initially focus more on risks from environmental factors as part of their broad ESG campaigns, especially from climate change. “Social” factors are only to become a stronger focus of European regulators in subsequent years. The EU Green Deal[vi] states that companies making “green claims” should back them up with a standard methodology to assess their impact on the environment. The EU Circular Economy Action Plan 2020[vii] requires companies to substantiate their environmental claims using product and organisational procedures for their environmental footprint.

Information on the environmental performance of companies and products across the EU should therefore become reliable, comparable and verifiable. Reliable environmental information would enable market participants – consumers, businesses and investors – to make greener choices and avoid greenwashing. A new EU taxonomy[viii] now regulates for the first time, among other things, the difference between “light green” and “dark green” investments[ix]. However, there are no uniform designation standards or labels worldwide, so the EU's initiative is to be welcomed.

Social (S) – socially and labour friendly: Apple Inc. shares are represented in numerous global sustainable tech funds, despite criticism around supplier countries with questionable human rights situations and low labour protection standards. How humane and fair are working conditions in mines, warehouses, manufacturing or subcontracting and along the entire supply chain? What proportion of suppliers can Apple trace on its own and what proportion of suppliers are from which companies in which jurisdictions/regions? Is Apple at all willing to monitor compliance with its own Code of Conduct and take appropriate action if there are anomalies or warnings from the supply chain? Rating providers such as Sustainalytics, Bloomberg ESG-Measure or MSCI largely exclude the supply chain/third-party supplier problem in their assessment and still focus on emissions and the direct corporate contribution to global warming. In our opinion, this is clearly not enough.

In its original version, the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (2021) was supposed to examine all supply chain members, but in its final version, it was limited only to direct suppliers. In the broader sense, this follows international standards such as the FCPA and UKBA. The idea behind it: Everyone is part of a supply chain and if everyone takes care of their immediate suppliers, the entire chain is covered. Thus, multiple sub-sourcing abroad is not directly in the scope of application – conflict materials as in the area of trade in goods are of course excluded and have to be considered accordingly. It remains to be seen whether the law will be reformed again with increasing EU regulation in line with the “social” factor.

Governance (G) – Corporate governance: “Good governance”, i.e., good, honest corporate governance that goes beyond merely managing potential risks from violations, meeting the minimum regulatory requirements, and relying as conservatively as possible on tried and tested procedures. Instead, governance reflects the ethics of the individual company and should set the culture in practice for the future with “tone from the top”. Negative examples of “tone from the top” were provided by the VW exhaust gas (Dieselgate) or works council affair, as well as the Wirecard case including the subsequent audit mess - they too were considered “sustainable investments” and failed due to disastrous management, scandalously flanked by gross breach of duty in office and insider trading by public officials on the part of the national supervisory authority.

The tension field of corruption

If ESG ethics already raise questions among DAX companies and German regulators because it is too vague, and if greenwashing allegations affect DAX corporations, as in the cases of DWS and VW, one may ask how the issue fares internationally along global supply chains, especially in countries with higher corruption rankings according to Transparency International.

Corruption – in all its forms – is one of the biggest challenges of ESG compliance and a truly material problem for investors, especially in times of crisis. It comes in many forms: bribery of public officials, taking or granting benefits, embezzlement, nepotism and finally frivolously working officials and lax or absent control structures. The latter pave the way for unfair dealings and illegal private arrangements by deliberately undermining independent audits, verifiable documentation and government bodies, or by condoning violations and their consequences. At its most extreme, it is systematic government official corruption that brings entire jurisdictions into disrepute. Inadequate governmental institutional integrity not only results in a loss of business and public trust but also in drastic environmental destruction, illegal wildlife trafficking, money laundering, terrorist financing – even modern slavery, child labour and human trafficking.

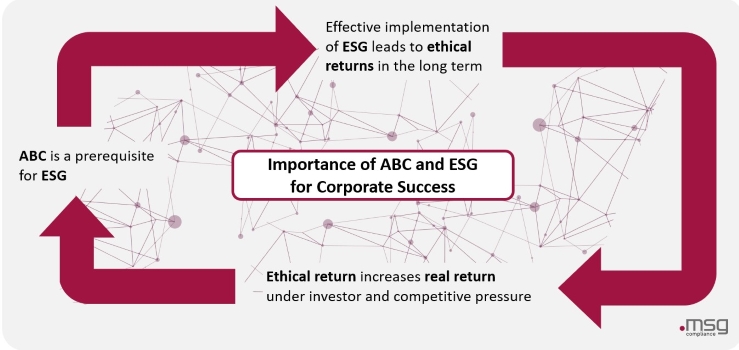

Corruption is capable of undermining all pillars of ESG. Therefore, effective ESG implementation along the supply chain and especially in the area of supply chain compliance requires an effective anti-bribery and corruption strategy. This applies in principle and is intensified in the international environment, especially in countries with a high structural state and private sector corruption risk.

Corruption has many faces

Corruption is very diverse, and money is not always involved. It does not follow the same patterns, which makes it all the more difficult to detect.

- Cash is truth: Direct cash payments were and still are tried and tested and difficult to detect

- Hospitality, travel and entertainment (e.g., pleasure trips by works councils)

- Gifts and gratuities: often undetected or dismissed as trivial, including non-monetary ones

- Favours for family or friends (e.g., the internship for the niece)

- Assurance of privileges, contacts (special permission, establishment of business contacts)

- “Media Bribe”: mutual favours between media/press representatives and politicians during election campaigns (e.g., positive media coverage in exchange for politically induced market power while distorting competition in the news or newspaper industry)

- Hush money: for not reporting, advertising, publishing

- Bribe, acceleration, or facilitation payments

- (Hidden) bribery in the form of charitable donations, also for third parties (charity, NGOs)

- (Hidden) bribery in the form of political donations, also for third parties

- Bribery in the form of commission payments

- Benefits and non-market conditions (loans, real estate, luxury goods, leisure activities, etc.)

- Bribery of public officials (in connection with, among others, tender fraud, authorisation, access to benefits)

- Misappropriation of state or company property

- Failure to comply with auditing, record-keeping, reporting obligations

- Procurement of fictitious services from shell companies (letterbox companies, also offshore)

Statistics

The current scale is estimated at USD 1.75 trillionx] in annual corruption payments and the resulting damage at USD 2.6 trillion (5% of global GDP).

In the health sector, corruption kills 140,000 children annually.

Up to 25% of public funds are lost annually because of corruption.

Governments pay USD 7.5 trillion annually for global health care, but corruption causes USD 500 billion (7%) to be lost. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), USD 370 billion would be enough to ensure access to health care for everyone in the world.[xi]

The World Bank and the World Economic Forum estimate that corruption increases business costs by 10% worldwide. According to Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and Transparency International, corruption increases contract costs in developing countries by 25%.

The UN report on corruption and the Covid pandemic at the G20 Summit in Riyadh warned that corruption remains a major threat to containment efforts, stating: “It is generally accepted that corruption thrives in times of crisis due to the conducive environments that are fed by disorder and confusion. [...] International bodies and institutions, including, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Economic Forum (WEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank, the Council of Europe's Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), the European Ombudsman, as well as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) called for countries to strive towards increased global vigilance and the integration of anti-corruption programming.”[xii]

A solution approach: business partner due diligence & anti-bribery & corruption (ABC)

- “Good governance” is important for investment in all industries and markets. Demonstrated culture and robust clear, segregated roles and responsibilities, a control design with adequate IT tools, up-to-date policies & procedures[xiii], as well as training tailored to the business help increase sensitivity to suspicious behaviour in organisations.

- The individual rating is important before aggregation to the overall rating in a fund/portfolio assessment. Each service provider contributes to the institution's overall ranking. The rating can include diverse data sources and risk assessments and aggregate these into a weighted score.

- ESG factors and the adequate handling of resulting risks must be integrated into business strategy, governance and risk management. For this purpose, the EBA for the first time gives uniform general definitions of ESG risks (EU Taxonomy Regulation) and identifies assessment methods for effective risk management.[xiv]

- Especially in countries and industries with known corruption problems, ABC prevention is an initial prerequisite for the effectiveness of ESG

- Focus on the culture in practice and ethics of the company and on the individual risk exposure of all its bodies, employees and third parties rather than on minimum regulatory requirements to avoid fines and other sanctions: Holistic risk management instead of exclusively legal compliance risk management!

- Implement whistleblowing systems that guarantee anonymity. The majority of tips come from internal and external whistleblowers.[xv]

- The maxim is:

Warnings & red flags

In addition to whistleblowing systems, conspicuous behaviour by the counterparty itself or transactions associated with it can provide indications of corruption. Know-your-customer/counterparty (KYC/KYX) and transaction monitoring systems should therefore be regularly checked for indicators, so-called “red flags”, with regard to anti-bribery and corruption, and should be re-parameterised or readjusted as necessary. Relationships between companies and traders must also be scrutinised.

- Counterparty receives disproportionate commissions (“fees-on-the-side”)

- Implausible payments for contingency fees (purpose, amount, place, principal, beneficiary, etc.)

- Receipt of implausible discounts (deviating from market conditions)

- Provision of alleged “consultancy services” to legitimise fictitious payments (vague description of the service provided or to be provided), business intransparency

- Implausible industry connection between principal and beneficiary

- Counterparty has business or close family ties to foreign officials or a Foreign Public Officer (FPO) or even a Politically Exposed Person (PEP) or their close associates, so-called “Relatives & Close Associates (RCAs)”

- Property purchase with unusual or no financing

- Overbilling (potentially with withholding of the difference)

- Payments for fictitious services to shell companies

- Request for transactions to offshore banks

- and many other

Conclusion

There had been allegations of corruption and abuse of office against members of the German Bundestag several times last year. Some Union politicians are alleged to have been involved in brokering activities and to have collected high commissions in deals with medical protection masks. In addition, there is a complex affair involving alleged bribes from Azerbaijan. The recent 2.4 million euros bribery allegation at BMW (2.7 million euros damage) involving a former executive for embezzlement and commercial bribery by a consulting firm also testifies to the topicality, extent, and drastic nature of bribery in Germany - in both the public and private sectors of the economy. In this regard, the Council of Europe said that recommendations from its 2014 evaluation report on the prevention of bribery and conflicts of interest had largely not been implemented, according to interim reports in 2017 and 2019. Overall, efforts in Germany had been assessed as “not satisfactory”. It remains to be seen whether the planned lobby register of the Bundestag for the often-criticised non-transparent dealings of lobbyists with politicians will remedy conflicts of interest in this course.

[i] Source Reuters

[ii] GSIA | (gsi-alliance.org)

[iii] www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/esg-assets-may-hit-53-trillion-by-2025-a-third-of-global-aum/

[iv] Abbreviation for Floating Point Operations Per Second, the number of floating point operations that a computing unit (processor or entire computer system) can perform per second

[v] See EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risks for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms (Jun 2021) and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SDFR), incl. funds categorisation light green/dark green article 8 + 9 and Regulation (EU) 2020/852 Sustainable Finance Taxonomy

[vii] https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/circular-economy/first-circular-economy-action-plan_en

[viii] EU Taxonomy according to Regulation (EU) 2020/852, anchored in the EU Sustainable Finance Action Plan, which aims to allocate more capital to environmentally sustainable activities

[ix] Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SDFR), incl. funds categorisation light green/dark green article 8 + 9

[x] http://transparency.org.uk/corruption-statistics

[xi] http://transparency.org.uk/corruption-statistics#_edn1

[xii] https://www.unodc.org/documents/corruption/COVID-19/G20_Compendium_COVID-19.pdf

[xiii] „Policies & Procedures” Frameworks for ABC, Fraud, Code of Conduct, Business Ethics, Conflicts of Interest

[xiv] The EBA report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risks for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms provides comprehensive recommendations such as ESG factors and ESG risks, in particular in relation to counterparties, to be integrated into the regulatory and supervisory frameworks for institutions and investment firms. In doing so, the report emphasises the importance of a holistic, forward-looking perspective and proactive approach by banks and supervisors. Starting with impacts of ESG factors and their implications for financial risks, it explains assessment methodologies for robust business models, risk monitoring indicators and effective ESG risk management, and identifies remaining data gaps and methodological challenges.

[xv] See EU Whistleblower Policy

Clan crime is currently one of the most explosive topics in Germany, both for the police and for society. Spectacular criminal cases, violence in public spaces, thematisation in TV series, the supposed loss of authority by the state due to lacking, insufficient or half-hearted intervention, parallel structures and the integration debate – a discussion as to whether the term clan does not already discriminate, ethicise or stigmatise – all this shows on the one hand the necessity of stronger combating, but on the other hand also the problems inherent in this part of organised crime (OC).

The term clan crime

The term "clan" is assumed to refer to family-like structures, which in reality, however, are broken up beyond kinship, e.g., in the course of migration, ethnic affiliation or economic gain.[1] Herein lies the explosive nature of the term and the accompanying criticism of racism, which is all too readily taken up by the perpetrators and used for a perpetrator-victim reversal. The association with clan structures from the Arab culture is leading. In our opinion, this is misleading because there are hardly any structural differences between Italian mafia clans, Russian, Polish or Arab clans. In order to lead the public discourse, but also for corresponding investigation, combating and prevention concepts, a descriptive term is needed.[2] This term was found in the form of "clan" and does not mean racial profiling.

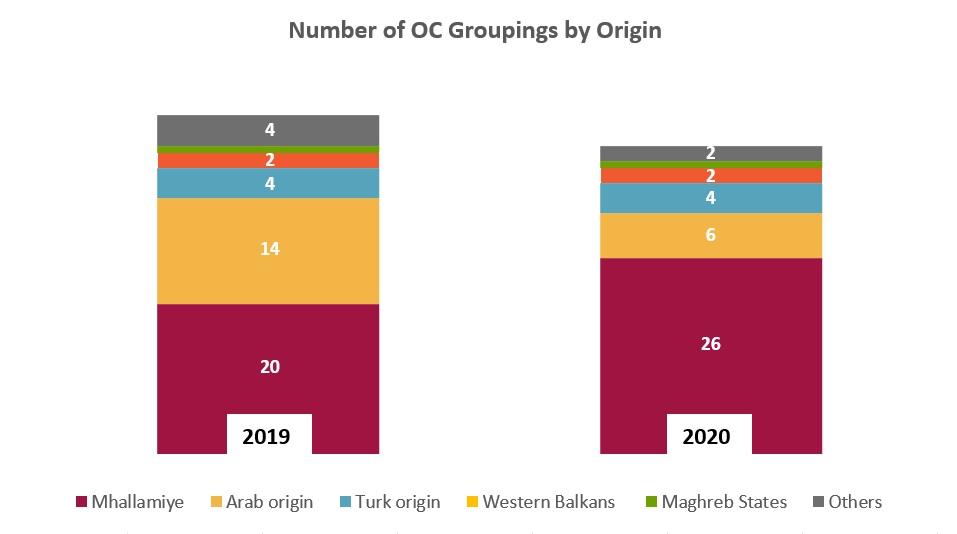

Figure: Distribution of clan crime within OC groupings by origin according to the Situation Report on Organised Crime of the German Federal Criminal Police Office

The Mhallamiye are also called "Lebanese Kurds" in Germany. Of the 41 clan crime groupings mentioned in the situation report, 26 can be attributed to them. This means that their share of the total number of clan crime groupings has increased from 44.4 to 63.4 per cent compared to the previous year, while the share of clan crime groupings of Arab origin has decreased significantly from 31.1 to 14.6 per cent.

In Germany, there are about 15,000 Mhallamiye Kurds. The largest Mhallamiye community in Europe, with about 8,000 members, is in Berlin. The second largest Mhallamiye community in Germany is in Bremen (approx. 2,500 people) followed by Essen/Ruhr (approx. 2,000 people).[3] The number of clan members is only an estimate, as different nationalities and different spellings of surnames do not allow for an exact classification.

Criminal clans that have achieved national notoriety are the Remmo family, which belongs to the Mhallamiye and counts about 500 members [4], and the Abou Chaker clan of Palestinian origin (also from Berlin), which is estimated to have 200-300 members[5]. The Miri clan, which also belongs to the Mhallamiye, consists of an estimated 2,600 people in Bremen alone and a total of 8,000 people nationwide. About half of them have already been investigated by the police. The Al-Zein family from Berlin, also belonging to the Mhallamiye and consisting of about 5,000 members nationwide [1], as well as the Goman clan from Leverkusen, which belongs to the Eastern European Roma, are known due to numerous headlines.[6]

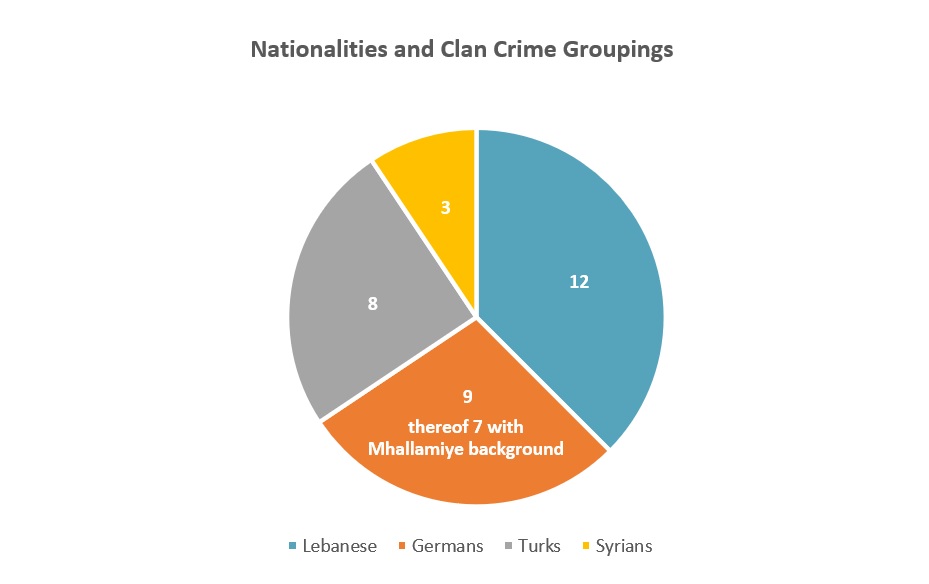

Figure: Dominant nationalities of decision-makers within clan crime groupings

Statistics on clan crime

The phenomenon of clan crime has been described in criminalistics since 2002. Criminal offences in connection with clan crime include organised property crime, narcotics and arms trafficking, human trafficking and (forced) prostitution, as well as serious violent offences and money laundering. Among the clans of Arab origin, the so-called hawala banking should be mentioned in particular. According to estimates by the German Federal Ministry of Finance, hawala banking generates up to 200 billion USD annually; the share of organised crime can only be guessed at.[7]

Since 2018, clan crime has been statistically recorded as part of organised crime. At the level of the federal states, e.g., in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and Lower Saxony, one can look up the State Situation Report on Clan Crime or consult the Federal Criminal Police Office’s (BKA) Situation Report on Organised Crime, in which clan crime is recorded as a separate sub-category.

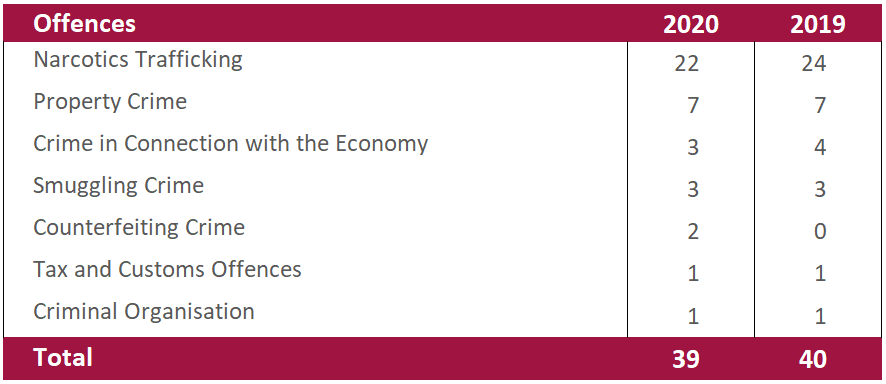

Table: The most frequent offences of the OC groupings in connection with clan crime[8]

It is important to point out that crimes committed by clans in the areas of general crime, offences against the Administrative Offences Act and brute force offences (such as robbery, assault) are not included in the Federal Situation Report.

This form of reporting shows a supposed decrease in crime. Supposedly, because these figures only represent the so-called bright field and the forms of organised crime, as well as white-collar crime, do not usually become known through criminal charges, but belong to the so-called control crime. Consequently, these must be investigated more on one's own initiative. Experts therefore assume that the figures in the situation reports of the State and the Federal Criminal Police Offices (LKA and BKA) are characterised by strong under-reporting.[9] The danger that arises from this is a decoupling of social perception, which extends to clan-dominated no-go areas and which stands in contrast to this form of crime statistics. Furthermore, it can be assumed that a thinning out of specialised OC departments, sufficient staffing both in the law enforcement agencies and in the judiciary makes use of the statistics for argumentative purposes. In any case, the figures themselves are in contrast to the findings of the Europol report on the Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA), which can be summarised very well with a quote from Catherine De Bolle, Executive Director Europol: "I am concerned by the impact of serious and organised crime on the daily lives of Europeans, the growth of our economy, and the strength and resilience of our state institutions. I am also concerned by the potential of these phenomena to undermine the rule of law.”[10] However, even the methodologically different LKA reports, which also include brute force offences, do not show a clear development or trend in the number of crimes or suspects, as the following example from NRW shows:

Figure: Development of clan crime in NRW from 2016-2020

The assessment of the development from the NRW Situation Report 2020: "The number of clan proceedings remains at a consistently high level of 20% of all OC proceedings."[11] However, the situation report comes to a rarely noticed, positive conclusion that the results of asset confiscation measures doubled in the reporting year.

This can be seen as a positive signal, as the measures necessary for this were introduced in 2017 and now seem to be increasingly bearing fruit. The asset confiscation regulated in the Code of Criminal Procedure was fundamentally amended in June 2017. Since then, courts and public prosecutors can more easily confiscate assets of unclear origin - even without having to prove a specific criminal offence. This quasi-reversal of the burden of proof is considered to be of great importance in the fight against organised crime.[12] With this reform, the German legislature fulfilled its obligation to implement the EU Directive on the Freezing and Confiscation of Instrumentalities and Proceeds from Crime in the European Union (EU Directive 2014/42/EU of 3 April 2014).

The introduced reversal of the burden of proof in asset confiscation has led to public prosecutors actually making greater use of this instrument. In 2018, the judiciary in Schleswig-Holstein ordered the confiscation of assets worth around 18 million euros. Of this, 14.5 million was confiscated for the benefit of the victims and 3.4 million fell to the state. In 2017, there had been only 2.26 million euros for the benefit of the victims and less than one million euros for the state.

There were similar developments in other states. This was the result of enquiries by the German news agency dpa with the ministries. For example, the Hessian judiciary also confiscated significantly more assets from criminal offences in 2018, with the total amounting to around 7.8 million euros, compared to just under 4.3 million euros the year before. In Rhineland-Palatinate, the courts ordered assets worth 13.01 million euros to be confiscated last year, compared to 2.12 million euros in 2017.[13]

In Italy, the reversal of the burden of proof for asset confiscation has existed for more than 20 years. It is not without reason that Italy is considered a model for the fight against organised crime. It is estimated that more than 17,000 properties, estates and companies have been confiscated since its introduction. The damage to the mafia has long been in the double-digit billions.[14] In 2019 alone, over 800 million euros were confiscated in Italy and distributed to non-profit organisations.[15]

When it comes to assessing the economic damage caused by clan crime, there is also no agreement between the individual situation reports and the European, international statistics. In Germany, the federal states of Berlin, North Rhine-Westphalia, Lower Saxony and Bremen are primarily affected by clan crime. According to the BKA report, more than half of all OC investigations were conducted in these federal states.

Subsequent offence: money laundering

Ultimately, all offences have in common that the origin of the generated wealth is to be concealed. This is where the offence of money laundering comes into play. Criminal clan members channel their illegal income into the economic cycle, "launder" it in order to disguise its criminal origin and to keep it out of the reach of law enforcement authorities.

According to experts, Germany is a paradise for money launderers. According to a dark field study by the University of Halle-Wittenberg, around 100 billion euros are laundered in Germany every year.[16] This works so well in Germany precisely because there is no upper limit for cash payments. Regardless of the price, everything - even luxury real estate - may be paid for in cash. Above 10,000 euros, the buyer only has to show proof of identity. Italy and France have an upper limit of 1,000 euros for cash payments. Spain with 2,500 euros and Greece with only 500 euros also have an upper limit. For these reasons, international money launderers specifically invest in luxury goods and real estate in Germany. After a subsequent resale, they launder their "dirty" money again. In this way, money that has been illegally earned finds its way back into the economic cycle via Germany.

This is where perceptions and social discourse on clan crime come into play:

- Questions of income and behaviour: How can young men afford luxury cars and thus unabashedly endanger the road traffic regulations? Likewise, the gangster lifestyle can be seen as an attractive counter-model to legal income generation as a behavioural issue. Whether in music or film or at the meeting places of young people in and with the corresponding milieu, this can be observed.

- Dominating cityscapes: Shisha bars, betting offices, gambling halls, barber shops, nail studios, tattoo studios, boxing and martial arts clubs - often (partly) legal business fields of clan crime for generating sales for illegal activities, but especially for money laundering. The same applies to an increasing extent to special forms of real estate development and real estate investments, in which the concealment of incriminated funds is in the foreground.

- No-Go-Areas: The aggression and intimidation potential of the clans and the resulting lack of perceived police presence in connection with the parallel societies run by clans lead to a lawless space according to German laws, the so-called no-go areas.

Outlook

Recently, the problem of clan crime has been included in the coalition agreement of the three new governing parties in Germany.[17] According to the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), it is now a matter of gradually breaking up criminal structures through a whole bundle of different approaches, whereby the focus should not only be on harsh sanctions, but also on patient social work.

In addition to the further intensification of asset confiscation measures, it is important to improve the staffing of the law enforcement agencies and the judiciary as well as the cooperation across states and to digitally network the FIU with the State Offices of Criminal Investigation.

The reorganisation of Section 261 of the Criminal Code in connection with the Anti-Money Laundering Act will also make it increasingly difficult to conceal incriminated funds, which will lead to increased suspicions and approaches for the prosecution authorities. In this context, the efforts in the regulation of cryptocurrencies are also positive, as Europol rightly points out the service orientation of the "criminal entrepreneurs" in general and that of the "virtual asset service providers (VASP)" in particular.

In summary, it can be shown that anti-money laundering has an important significance in the fight against clan crime, which with specific patterns - similar to the Italian mafia families - can also master the challenges of the Lebanese, Arab and Turkish clans.

[1] For more information on the concept of clans in criminalistics, please refer to the understanding of the term in the framework concept of the State Criminal Police Office in Lower Saxony [Landeskriminalamt Niedersachsen (2019), Lagebild Clankriminalität – Kriminelle Clanstrukturen in Niedersachsen, page 5] and the National Situation Report on Organised Crime of the German Federal Criminal Police Office [Bundeskriminalamt (2019), Bundeslagebild Organisierte Kriminalität, page 30].

[2] Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Nr. 434, Clankriminalität als Gefahr für die Innere Sicherheit (I), April 2021, page 5

[3] www.mi.niedersachsen.de/aktuelles/presse_informationen/clan-kriminalitaet-sogenannter-mhallamiye-kurden-115576.html

[4] www.praxistipps.focus.de/clans-in-deutschland-von-abou-chaker-ueber-miri-bis-remmo_116032

[5] www.sueddeutsche.de/panorama/verhaftung-clanchef-abou-chaker-clan-1.4289117

[6] R. Ghadban, Arabische Clans-Die unterschätze Gefahr, 2020, page 162

[8] Bundeslagebericht Organisierte Kriminalität 2020

[9] Bannenberg, B. (2020), Wer sucht der findet … Fehlende OK-Ermittlungen; in: KriPoZ 4/2020, page 206

[10] European Union (2021), Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment, page 7

[11] LKA Nordrhein-Westfalen, Clankriminalität – Lagebild NRW 2020, page 3

[12] Dienstbühl, D. (2020), Die Bekämpfung von Clankriminalität in Deutschland: Verbundkontrollen im kriminalpolitischen und gesellschaftlichen Diskurs, in: KrPoZ 4/2020, page 214

[13] www.lto.de/recht/justiz/j/vermoegensabschoepfung-straftaten-staatsanwaltschaften-reform-in-der-praxis-bewaehrt/

[14] www.deutschlandfunk.de/italien-angriff-auf-das-vermoegen-der-mafia-100.html

[15] www.zdf.de/nachrichten/wirtschaft/geldwaesche-paradies-deutschland-100.html

[16] www.bussmann.jura.uni-halle.de/forschung/abgeschlossene_projekte/geldwaeschestudie_i_/

[17] Coalition agreement (www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf), page 107

Another financial scandal that has outraged people worldwide. As usual, those involved are the rich and powerful who use letterbox companies in tax havens to hide their assets from the tax authorities. The most explosive aspect of the revelation of the Pandora Papers was the involvement of high-ranking politicians, whose job it is to prevent this kind of economic crime. Dubious offshore transactions by more than 330 politicians and public officials from almost 100 countries are documented in the Pandora Papers. The outcry was great, for it is not the first scandal of this kind. The best-known case was the Panama Papers published in 2016, but the Luanda Leaks (2020), Paradise Papers (2017) and Lux Leaks (2014) also revealed dubious dealings in so-called tax havens.

In retrospect, the question arises whether and what has happened at the legal and regulatory level after the aforementioned revelations. This blog post sheds light on the impact of the Panama Papers. For this purpose, we will take a closer look at regulatory developments before and after the revelations of the Panama Leaks in order to be able to draw conclusions about their influence.

What problems were revealed by the Panama Papers?

The Panama Papers data leak was published in April 2016. It revealed that complex ownership structures were used to conceal criminal activities and evade tax obligations. The documents showed that transparency regarding the actual beneficial owner of certain legal entities needs to be improved and that a closer international cooperation is needed as well. At the same time, pressure was put on governments and judicial authorities to tackle the culprits – and there were calls for stricter regulatory requirements worldwide. Some of the politically exposed persons (PEPs) named in the documents had already been on international lists or had previously appeared as "special interest persons".

Through the analysis of the leaks, more than 38.4 million euros in back taxes were collected in Germany alone, and a further 19 million euros through criminal prosecutions.[1]

Regulatory developments prior to the publication of the Panama Leaks

Even before the publication of the Panama Papers, the EU Commission saw the need for more transparency with regard to the ownership of legal entities. Therefore, the 4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive[2] (4th AMLD), which entered into force in June 2015, included a comprehensive framework for the collection, storage and access to information on the beneficial owners of companies, trusts and other forms of enterprise. Member states were required to establish national registers of beneficial owners in order to make certain ownership relationships more transparent.3

Germany's reaction to the Panama Leaks

At the time of the publication of the Panama Leaks, the transposition deadline of the 4th AML Directive had not yet expired. Under pressure from the revelations, the German government presented a 10-point paper. The most far-reaching proposal contained therein was the demand for the implementation of globally networked registers that would keep the names of the persons who are actually behind the companies and profit from their earnings. This approach had already been agreed upon with the 4th AML Directive of the EU but not yet transposed into national law in Germany. In fact, the implementation of publicly accessible registers at EU level was not initially advocated from a German perspective. [3]

A new approach in the 10-point paper was the push to network these registers as much as possible and to make the information available to tax authorities and specialised journalists. Another demand related to the exchange of tax information between states. However, this idea was not entirely new, as the OECD had already been working on this topic for some time. An innovative proposal within the framework of the 10-point plan was the tightening of the statute of limitations for tax offences. The limitation period should only begin to run once a taxpayer has fulfilled their information obligations.

The result of the proposed action plan was sobering. The Tax Justice Network (TJN) published a review in April 2017, in which it became clear that only one proposal (statute of limitations for tax offences) of the ten points had been fully implemented. It criticised the suitability of the proposals to achieve significant success in the fight against money laundering, institutional corruption or letterbox companies. [4]

Introduction of the German legislation to combat tax avoidance

One consequence of the publication of the Panama Leaks was the introduction of the law on combating tax avoidance (Steuerumgehungsbekämpfungsgesetz - StUmgBG), which was passed in June 2017.[5] This was preceded by a discussion on the avoidance of taxation by means of the establishment and use of domiciliary companies (so-called letterbox companies), most of which are located abroad. Some of the amendments contained therein were due to ECJ case law/EU Commission.[6] In order to determine the taxable events, extended obligations to cooperate were introduced both for the taxpayers themselves and for third parties (banks). The new investigative powers of the tax authorities should make it easier to identify domiciliary companies in the future. The law should also have a preventive effect due to an increased risk of detection.

The core of the draft law was the creation of transparency regarding "controlling" business relationships of domestic taxpayers with business partnerships, corporations, associations of persons or assets with registered offices or management in states or territories that are not members of the European Union (EU) or the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) (so-called third-country companies).[7] Criticism was voiced during the consultation of the professional associations that the new regulations refer to all third-country companies and not only to those that do not develop their own economic activity.[8] Furthermore, it was criticised that the limitation to third countries outside the EU and EFTA excludes many problematic companies or structures, especially in Liechtenstein and Switzerland.[9]

The objective of the anti-tax avoidance law to fight the use of offshore letterbox companies is fulfilled by the new regulations. All relationships with third-country companies – irrespective of their economic activity in the case of certain control or determination relationships – are covered by the notification obligations. The journal of the German Economic Criminal Law Association (Wirtschaftsstrafrechtliche Vereinigung e.V.) sums up that the double fulfilment of the obligations to cooperate or notify in connection with third-country companies (taxpayers on the one hand, reporting entities on the other) and a broad interpretation of the prerequisites, which is in practice for precautionary reasons (in particular because of the liability risk according to § 72a AO), will lead to another flood of data for the tax authorities. This must be processed in addition to the information to be expected from the automatic exchange of information that is starting up.[10]

Reaction at EU level to the Panama Leaks

After the publication of the Panama Papers, the 4th AML Directive, which had just come into force, was examined more closely. It became clear that the newly created transparency requirements were not sufficient.

At the European level, too, there was a quick reaction to the publication of the Panama Papers. As early as July 2016, the Commission presented its proposal to revise the existing Money Laundering Directive on the occasion of the Panama Papers revelations and the terrorist attacks[11] that had taken place in Europe in the meantime. The proposal included stricter rules to prevent tax avoidance and money laundering which should further tighten the existing directive. For example, it called for public access to registers of beneficial owners and the expansion of information available to companies. In addition, there was also the proposal to interconnect the registers in order to improve cooperation between the member states.[12] At the same time, the EU Commission published a communication in which it wanted to promote transparency in the tax area and combat the abusive use of tax practices.[13]

Appeal for faster implementation

The Commission's proposals contained relevant approaches to improving the 4th AMLD. As the transposition deadline (26 June 2017) had not yet expired at the time of publication, the Commission called on the member states to take the proposed targeted amendments into account in their transposition and to bring it forward – if possible – to the end of 2016. The aim was to implement the urgently needed correction to the existing legal framework as quickly as possible.[14]

Implementation of the transparency requirements of the 4th EU AML Directive in Germany

The fourth edition of the European Anti-Money Laundering Directive required, among other things, the introduction of business registers. They should list the true beneficial owners of companies and avoid letterbox companies run by straw men, that appeared in large numbers in the Panama Papers.[15]

As of 26 June 2017, an electronically managed transaction register was created in Germany for the first time in the course of implementation. This was intended to prevent criminal actors from being able to hide behind corporate structures such as letterbox companies.[16] Germany introduced a backup register. Only legal entities under private law and registered partnerships that were not already listed in other subject registers had to register in the newly introduced backup register, otherwise the reporting fiction according to §20 section 2 of the German Anti-Money Laundering Act (GwG) applied.[17] The register was not public, so that only persons with a "legitimate interest" were to be granted access. Consequently, the implementation did not fulfil the 10-point plan's demands for the time being.

Thus, the transparency register did not live up to its name, as company holdings in Germany remained mostly opaque. Although the Federal Republic introduced a register, it was already foreseeable at that time that a new reform would be necessary. Thus, Germany did not follow the Commission's call to bring implementation forward. Likewise, no reference to the Panama Papers or the Commission's proposal could be found in the explanatory memorandum[18] – certainly not surprising from the EU's point of view. In the past 20 years, two EU infringement proceedings have been initiated against Germany for slow implementation of money laundering regulations. In 2014, the FATF threatened to treat Germany as a high-risk country in the future, among other things because of insufficient precautions against terrorist financing.[19] The FATF audit report also makes it clear that Germany was not in full compliance with FATF regulations regarding the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing as early as 2010.[20]

5th EU AMLD: Changes at a glance

The tightening of the 4th AMLD planned by the EU Commission resulted in the 5th AMLD in May 2018.[21] As an amending directive, it builds on the content of the 4th AMLD and tightens its regulations. Looking at the content of the directive, it becomes clear that the Commission's proposals have been integrated into a legal framework that has a binding effect. In retrospect, the Commission's appeal to take into account the specific changes it proposed in the implementation of the 4th AMLD shows for Germany that an appeal was not sufficient to induce member states to act. Only a directive was effective in obliging the member states to take action. The contents of the 5th AML Directive were, among other things, to further improve transparency with regard to the beneficial owner. This included the extension of access rights and the international networking of the transparency register.[22]

Implementation in Germany

The 5th AML Directive entered into force in July 2018 and had to be transposed into national law by the member states by 10 January 2020. In the explanatory memorandum[23] of the draft law, explicit reference was made for the first time to the Panama Papers.[24] The introduction finally adjusted access to the transparency register. Now, all members of the public have the opportunity to inspect it; no longer only those who can provide proof of legitimate interest.[25] This illustrates that with the implementation of the 5th AML Directive, the plans derived from the Panama Papers regarding the expansion of the transparency register have been legally implemented from a regulatory perspective.

The realisation of the originally required transparency and networking did not take place until August 2021. Through the implementation of Directives (EU) 2015/839 (Anti-Money Laundering Directive) and (EU) 2019/1153 (Financial Information Directive), the already introduced transparency register was converted into a full register. As a result, the so-called reporting fiction was abolished for the first time. Obliged legal entities pursuant to §20 Section 1 AMLA, legal persons under private law and registered partnerships as well as foundations without legal capacity pursuant to §21 AMLA must not only identify their beneficial owner but also explicitly report it to the transparency register due to the reporting fiction abolished by the German Transparency Register and Financial Information Act (TraFinG). Finally, a register network was created at EU level, which is intended to facilitate communication between the member states.[26]

Conclusion

Germany's efforts in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing have a lot of room for improvement. Although the finance minister at the time had already drawn up a 10-point plan in April following the publication of the Panama Papers, it was not fully implemented. This year's FATF audit of Germany will show us the current status of Germany with regard to the implementation of international standards in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing in the final report. This is expected to be published in June 2022.

At the Anti-Corruption Summit in London on 12 May 2016, which took place after the publication of the Panama Leaks, 40 countries and six organisations came together to declare war on international corruption. Many countries took promising steps to fight corruption. Germany, on the other hand, did not want to introduce publicly accessible registers at that time.[27]

Looking at Germany's action plan, it was already vulnerable at the time of publication, as it did not appear sufficient in terms of its feasibility or effectiveness. With regard to transparency, even the uniform Commission proposals did not move Germany to act more quickly. Until recently, Germany only implemented the minimum required at EU level.

Even though the implementation took five years (2016-2021), the goal was achieved. The transparency register is not only publicly accessible and filled with complete data sets, but also networked at EU level. How effective this implementation will be has not yet been conclusively clarified and will have to be further monitored (see also "From a Backup Register to a Full Register – Are the Alterations by the German Act TraFinG Enough?").

Ultimately, the legislator should also question whether more transparency alone will be sufficient, or whether the question of the raison d'être of nested corporate structures should be addressed in order to get to the root of the problem.

It remains exciting to see what consequences will be drawn from the Pandora Papers and what other revelations will follow in the future. It is clear that the Panama and Pandora Papers are only the tip of the iceberg. Even if there have been international successes in the fight against money laundering (such as the uncovering of the money laundering scandals of the Latvian ABLV Bank[28] or the Spanish Banca Privada d'Andorra[29]), it remains to be said that there is still a long and rocky road full of hurdles ahead of us to discover all abuses and close loopholes.

Whether the investigations of the Pandora Papers come to the conclusion that they are legal tax avoidance schemes or illegal tax evasion, money laundering, state looting (keyword "kleptocracy") or other offences, the courts will have to decide. However, the Panama Leaks show us that such revelations can provide an impulse for further development of the legal framework. And they confirm to us that we still have potential for improvement in the speed and effectiveness of implementation.

[1] https://www.wiwo.de/politik/deutschland/steueroasen-millionen-zusaetzliche-steuern-durch-auswertung-der-panama-papers/26920234.html

[2] Directive (EU) 2015/849

[3] https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/MeinzerTrautvetter2017_Bilanz-Aktionsplan-Schäuble-1.pdf

[4] https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/MeinzerTrautvetter2017_Bilanz-Aktionsplan-Schäuble-1.pdf

[6] https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Gesetzestexte/Gesetze_Gesetzesvorhaben/Abteilungen/Abteilung_IV/18_Legislaturperiode/Gesetze_Verordnungen/2017-06-24-Steuerumgehungsbekaempfungsgesetz/1-Referentenentwurf.pdf

[7] https://datenbank.nwb.de/Dokument/635732/

[8] BT printed matter 18/11132, 15

[9] https://wi-j.com/2018/02/22/das-steuerumgehungsbekaempfungsgesetz-neue-datenmassen-fuer-die-finanzverwaltung/

[10] https://wi-j.com/2018/02/22/das-steuerumgehungsbekaempfungsgesetz-neue-datenmassen-fuer-die-finanzverwaltung/

[11] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0050&from=EN

[12] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/MEMO_16_2381

[13] https://rsw.beck.de/cms/?toc=ZD.ARC.201607&docid=379718

[14] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_2380

[15] https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/panama-papers-geldwaesche-auch-in-deutschland-ein-grosses-problem-a-1085980.html

[16] https://www.validatis.de/kyc-prozess/news-fachwissen/5-eu-geldwaescherichtlinie/

[17] https://www.msg-compliance.de/en/blog-item-en/from-a-backup-register-to-a-full-register-are-the-alterations-by-the-german-act-trafing-enough

[18] https://www.bva.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Aufgaben/ZMV/Transparenzregister/entwurf_gesetz_umsetzung_geldwaescherichtlinie.pdf

[19] https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/panama-papers-geldwaesche-auch-in-deutschland-ein-grosses-problem-a-1085980.html

[20] https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer/MER Germany full.pdf

[21] Directive (EU) 2019/1153

[22] https://www.validatis.de/kyc-prozess/news-fachwissen/5-eu-geldwaescherichtlinie/

[23] Printed matter 19/13827

[24] https://www.bva.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Aufgaben/ZMV/Transparenzregister/gesetz_umsetzung_aenderungsrichtlinie.pdf

[25] https://www.ey.com/de_de/financial-accounting-advisory-services/das-neue-gwg-was-sich-durch-die-5-eu-geldwaescherichtlinie-aendert

[26] https://www.msg-compliance.de/en/blog-item-en/from-a-backup-register-to-a-full-register-are-the-alterations-by-the-german-act-trafing-enough

[27] https://www.weed-online.org/presse/10074969.html

[28] https://www.luzernerzeitung.ch/wirtschaft/dubiose-geschaftspartner-wieso-banken-das-risiko-zunehmend-scheuen-ld.1495062

[29] https://taz.de/Spanische-Banco-Madrid-ist-Pleite/!5016479/

The National Situation Report on Organised Crime 2020, published by the German Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), puts Russian-Eurasian organised crime back in the spotlight. In the following, we will take a detailed look at this and at those countries in which Russian influence is still noticeable to this day due to their special geographical location and history.

The legacy of the Soviet Union reverberates. How do you come to this realisation? By reading the current BKA report on organised crime (OC), which devotes a separate chapter to the topic of REOC. REOC stands for Russian-Eurasian Organised Crime.[1] In order to do justice to this topic, it is important to begin by briefly discussing the ideology that shapes REOC groups. This is the so-called ideology of “thieves in law” – an explicitly granted formal and special status of a “criminal authority” or a professional criminal. This person occupies a special position among initiated criminals in the world of organised crime or even correctional institutions, and then also exercises informal authority over members of lower status. A subculture of its own exists, which formed a specific code of values and norms during the Soviet era and to which the syndicates of the post-Soviet states feel bound.[2] The post-Soviet states are, as the name suggests, the successor states of the former Soviet Union and include a total of 14 other states in addition to the Russian Federation: The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), but also Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and finally Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

The BKA report describes REOC structures as follows:[3]

- They are dominated by individuals who were born in a state whose territory had once been a part of the Soviet Union and have experienced cultural and social ideals of separation, strength and determination in the context of crime.

- They are dominated by individuals who were born outside the successor states of the Soviet Union, but who feel committed to and belong to the aforementioned ideals because of their culture, history, language, traditions and ancestors.

Overall, according to the report, the number of OC proceedings in the area of REOC has hardly changed compared to the previous year (from 27 to 26). Two thirds of the REOC proceedings involved primarily German, Russian and Lithuanian nationals. 12 out of 26 REOC proceedings were dominated by individuals with Russian citizenship.[4] The most frequent offences with regard to REOC concerned crimes related to business and narcotics offences.[5] What is striking about the figures in the report is that – especially considering the size of the population – a high proportion of Lithuanian citizens is suspected in OC proceedings with a REOC background, which is more than 20%. The Baltic state counts (despite its glorious past as the once largest state in Europe in terms of area)[6] less than 3 million inhabitants. Today, Lithuania borders with both Russia (through the enclave of Kaliningrad (formerly Königsberg)) and Belarus. Until its independence in 1990, it was occupied territory of the Soviet Union. This special constellation, which is due to the turmoil of the centuries, predestines Lithuania to be a hub of trade between the EU and the more eastern successor states of the Soviet Union. The port of Klaipeda, among others, is of particular importance here. The same applies to the other two Baltic states; Latvia, with its borders with Belarus and Russia, and Estonia, with its borders with Russia, are additional hubs of eastern trade.

The importance of the Baltic States as a hub is reinforced beyond the geographical conditions by the special composition of their population. Even though Lithuania has only a small percentage of ethnic Russians of about 6%, this is concentrated in the capital Vilnius, the political and economic centre of the country. In Latvia and Estonia, due to Moscow’s active population policy during the period of Soviet rule[7], this proportion is significantly higher and amounts to more than 25% in each case.[8] Therefore, it is not surprising and only logical that even after more than 30 years of independence there are still strong economic ties with Russia as the main successor state of the Soviet Union. In this context, it should be noted that only Estonia has managed to turn a little more towards the Scandinavian region in the meantime. Finland and Sweden are the main export partners for the small country in the northeast, but trade with its eastern neighbour remains important.[9] The totality of the listed connections that interweave the Baltic States with the Russian-speaking area (simplified as the territory of the former Soviet Union) has certainly contributed to the fact that Estonia and Latvia in particular, but also Lithuania[10], have repeatedly found themselves unwantedly in the international media over the last 15 years. Criminal actors, especially from Russia[11], Azerbaijan[12] and Moldova[13], have misappropriated the banking systems of the Baltic states in order to launder dirty money. In the following, this circumstance will be taken into account and a short overview shall be allowed, starting with the northernmost state Estonia.

ESTONIA

With regard to the topic of money laundering and Estonia, the Danske Bank scandal with its unbelievable dimensions, which came to public attention in 2017-18, attracted a great deal of attention in the international media and the banking scene. It is possible that more than 200 billion euros were laundered here in the period 2007-2015. A large part of the money originated in Estonia, Russia, Latvia and Cyprus. In the course of subsequent investigations, possible links to the Russian president's family, the Russian domestic intelligence service FSB and the Azerbaijani presidential family were hinted at.[14] Danske now considers a large part of these funds to be suspicious and of criminal origin – for example from tax evasion or drug trafficking. According to research by the Financial Times, however, internal alarm bells should have rung here early on. In 2008, for example, only 0.5% of Danske Bank’s total assets were attributable to its Estonian branch. Corporate sales by non-Estonians, however, accounted for 8% of pre-tax profits. The Estonian supervisory authority as well as the Russian central bank had already informed the bank at that time that some of its clients would engage in questionable transactions. Still, nothing happened on the part of Danske and so the record sum of 32 billion euros was moved through the branch’s “non-resident” portfolio in 2013. Things only started to move when an internal whistleblower initiated an internal audit in the same year, which led to the dissolution of the “non-resident” business branch in Estonia in 2016.[15] [16] So far, the scandal has resulted in the closure of Danske’s Estonian branch and the imprisonment of 10 former employees of the concerning branch. The CEO active at the time of the scandal had to resign.[17]

LATVIA