You'd like to find out more about the range of services offered by the msg group? Then visit the websites of msg and its group companies.

On 21 November 2021, Turkey was placed on the so-called “grey list” by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)[1] alongside Mali und Jordan because its anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) measures were assessed as insufficient.[2] The grey list is a global list of countries that have insufficient safeguards against money laundering, proliferation and terrorist financing.

Why was Turkey included in the grey list?

Turkey is one of the member states of the FATF and has thus committed itself to the fight against financial crime. In the FATF’s view, the country has made some progress in the past, but according to FATF President Marcus Pleyer, numerous problems remain.[3]

The FATF concretised its criticism in its press release of 21 October 2021. The main criticism was that the country’s supervision did not take sufficient action against high-risk sectors such as banks, gold and gemstone traders as well as real estate agents. It is feared that terrorist groups, among others, feed their illegally acquired funds into the Turkish real estate market and integrate it into other sectors from there. Due to the geographical proximity to Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon and the relatively permeable borders to Turkey, there is also the concern that terrorist financing does not stop at the gates to Europe.

Furthermore, the FATF reacted with the “grey listing” to the ongoing harsh approach towards the civilian population. Specific criticism is directed against Turkey’s “Anti-Terror Law” to “prevent the proliferation of the financing of weapons of mass destruction.” Contrary to the title, the law does not contain penalties or control mechanisms against money laundering or the financing of weapons of mass destruction for terrorist purposes. Instead, it entitles the president to freeze the funds and assets of terror suspects.

Ultimately, Turkey’s handling with non-profit organisations was also at the centre of the FATF’s criticism. The mere existence of criminal investigations on terrorism allegations against a board member of an initiative, association or foundation entitles the Ministry of Interior and the government-appointed governors to suspend the person concerned, paralyse the activities of the respective association and appoint an official receiver in their place.

What are the consequences for Turkey of its inclusion in the grey list?

Turkey’s inclusion in the FATF’s grey list means that it is under increased scrutiny. At the same time, it is obliged to

- cooperate with the FATF

- launch an action plan[4] which resolves the certified deficiencies in the area of anti-money laundering and anti-terrorism

- adhere to its action plan (implementation will be monitored)

Specifically, the FATF demands Turkey to ensure a risk-based approach for the supervision of non-profit organisations in line with the FATF standards in the future. However, legitimate activities should not be prevented or hindered by the authorities.[5]

What are the consequences of the “grey listing” for obliged entities under the German Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA)?

The FATF does not impose any direct obligations on its members to take action against “grey” listed countries. However, the members are asked to take the FATF information into account in their risk analyses and to take further measures if necessary.[6]

This has far-reaching consequences. First of all, all obliged entities according to Section 2 of the German Anti-Money Laundering Act (GwG) must react as quickly as possible to Turkey’s inclusion in the grey list and adapt their risk analyses. Internal security measures must be derived from the results of the risk analysis and be implemented. The specific scope of the measures to be taken is determined by the obliged entities themselves.

For companies that maintain business relations with Turkey and for companies based in Turkey, enhanced due diligence obligations may apply. One may criticise the fact that neither the Federal Ministry of Finance nor BaFin have made any clear recommendations on this matter at this point in time, although this would be permissible under the German AMLA (Section 15 (8)). However, enhanced due diligence obligations are already derived from Section 15 (2) GwG.

What are the consequences for correspondent banking business?

Turkey’s inclusion in the grey list may put a strain on its relationship with foreign banks and investors. States that maintain business relations with Turkey may have to conduct due diligence audits significantly more often, taking into account the risks of working with Turkish banks.

The German Anti-Money Laundering Act (GwG) defines a catalogue of mandatory due diligence for the correspondent banking relationships, which consists of general due diligence obligations and, under defined conditions, additional enhanced due diligence obligations.

Turkey’s “grey listing” could also entail enhanced due diligence audits. Obliged entities under the German Anti-Money Laundering Act (GwG) should check whether their supply chains pass through Turkey or another “grey” listed country. Checking Turkish government officials or state-owned companies against sanctions lists, for example, is also an option for enhanced due diligence.

What effects does the grey list have on supply chain relationships?

From 2023, German companies will be obliged to identify and eliminate risks to human rights and the environment as well as violations of protected legal positions along their supply chains. The German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG) requires this under certain conditions. Here too, the fact that a country is on the grey list must be taken into account when conducting a risk analysis. Based on a risk-based approach, companies must decide how far down the supply chain they want to extend their due diligence. This also raises the question to what extent due diligence obligations can be imposed on the direct contractual partner to check the other companies in the supply chain. “For companies on international terrain, the regulatory expectations are relatively clear. The need and requirements for effective business partner managements are comprehensively set out in the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the UK Bribery Act (UKBA), for example.”[7]

What are the impending economic consequences of the FATF classification?

The Turkish lira is on a downward trend and inflation is close to 20 per cent. Foreign investment in Turkey is declining. The inclusion in the grey list may have devastating consequences for Turkey’s already struggling economy, as it is likely to have an additional deterrent effect on foreign investment and trade flows.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has confirmed in a study[8] that a listing on the FATF’s grey list has a large and significant negative effect on a listed country’s capital inflows: incoming capital flows – both foreign investment and bank transfers – decreased by an average of 7.6 per cent of gross domestic product.

This will most likely be accompanied by an even stronger trend towards cryptocurrencies, which are attractive to many Turks, in order to escape the further decline of their own currency.

Conclusion

The inclusion of a state in the grey list is often seen by experts as the first step to stricter sanctions. In the case of Turkey, the grey listing possibly also creates pressure on the EU to include Turkey in its own money laundering list.[9] Transparency International suspects that, as a next step, Turkey could face sanctions from the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and difficulties in securing loans.

Companies trading with Turkish business partners are now subject to special due diligence obligations. Obliged entities under the German Anti-Money Laundering Act (GwG) should compare their risk assessments for all countries with the FATF’s grey list and adapt their risk analyses. Otherwise, this may lead to violations of the GwG.

The FATF’S grey list has negative implications for the listed country. However, it can also be seen as an incentive to initiate reforms in order to resolve existing deficiencies in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing and to generate capital flows into the country again.

[1] The FATF is the world-leading anti-money laundering organisation. It develops guidelines, sets standards and makes recommendations to combat money laundering, terrorism financing and the financing of weapons of mass destruction (proliferation). More than 200 states – including Turkey – and jurisdictions have committed themselves to compliance of FATF standards. The implementation of the measures by the member states is regularly reviewed by the FATF.

[2] Turkey had previously been added to this list in 2011 and removed in 2014.

[3] https://anfdeutsch.com/aktuelles/turkei-auf-grauer-liste-fur-finanzstraftaten-28920

[4] Meanwhile, Turkey has formulated an action plan. Its content can be read here: www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/high-risk-and-other-monitored-jurisdictions/documents/increased-monitoring-october-2021.html

[5] www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/high-risk-and-other-monitored-jurisdictions/documents/increased-monitoring-october-2021.html

[6] www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/high-risk-and-other-monitored-jurisdictions/documents/increased-monitoring-october-2021.html

[7] www.catuslaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Trossbach_CCZ-Geschaeftspartner-Compliance.pdf

[8] www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/05/27/The-Impact-of-Gray-Listing-on-Capital-Flows-An-Analysis-Using-Machine-Learning-50289

[9] www.mena-watch.com/tuerkei-koennte-auf-graue-liste-fuer-korruption-und-geldwaesche-kommen/

The Financial Intelligence Unit's (FIU) Annual Report shows that in the period March to December 2020, around 11,200 suspicious activity reports (SARs) were filed in relation to Covid-19 emergency assistance wrongly paid by obliged parties. Of these, the FIU identified around 9,500 reports as attempted fraud.

This development was foreseeable as the Covid-19 emergency assistance could be applied for at short notice and in a relatively uncomplicated manner by German standards and is not subject to repayment. Thus, it could be assumed that established typologies such as the use of so-called straw men would also be used to illegally obtain Covid-19 emergency assistance.

It is equally unsurprising that, as can be seen from the annual report, the circle of participants is not limited exclusively to straw men, companies that had already been insolvent or in liquidation, but also includes companies that had not suffered any pandemic-related losses. Applications also came from private individuals who had not registered a business or from welfare recipients used by third parties. This phenomenon also exists in connection with activities as a financial agent and may be assumed to be known.

For the FIU Annual Report 2021, it will be exciting to see whether cases will be addressed in which, for example, politically exposed persons (PEP) wanted to draw financial benefits from the pandemic - such as the cases of the CDU politicians Niklas Löbel or Georg Nüßlein, who are said to have received high commissions from mask transactions.

The FIU's case presentation on trade-based money laundering (TBML; see also separate blog article on this) in the context of Covid-19 is also noteworthy. It clearly shows obliged parties, using a concrete example, that fraudulent acts do not involve cases with amounts between 3,000 and 25,000 euros only. In connection with the import of respiratory protection masks from Asia, a credit institution stopped a suspicious payment of 1.6 million euros before it was transferred abroad and reported it to the FIU. This case impressively shows that the implemented measures for the purpose of money laundering prevention seem to have had their effect in this institution.

It should also not be forgotten that, at times, the disbursements were stopped due to a large number of false applications, which at least in North Rhine-Westphalia may have led to a higher sensitivity in the context of the approval. However, it is no longer possible to determine how many cases of damage were prevented. At this point in time, the German Association of Judges speaks of more than 20,000 cases in connection with emergency assistance fraud and other pandemic-related offences.

Source: FAZ

It can be assumed that the number will continue to rise in the coming months and years. We will also have to expect more spectacular cases and irregularities in connection with Covid-19 in the future. This is shown by the cases of suspected billing fraud in rapid tests, which are assuming ever greater proportions and continue to be the focus of investigating authorities.

Source: ZEIT

What is striking here is that the investigating authorities were apparently only made aware by the media that the number of reimbursements applied for was not in line with the number of rapid tests actually carried out. It is thanks to the research activities of the media that these cases have come to the attention of the general public.

It would be welcome if the FIU, in its Annual Report for 2021, not only communicated the number of SARs in connection with Covid-19, but also presented how many unjustly flowed funds were seized by the investigating authorities. In this way, it could provide the obliged parties with feedback that their efforts were crowned with success, because the mere number unfortunately does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the seized volume.

Hawala banking, also known as "underground banking", has a centuries-old tradition and exists in many countries as a parallel system to traditional banking. The fact that this system can also be used for the purpose of money laundering or international terrorist financing is not a new discovery. The FIU has now taken up and addressed this unregulated money transfer in its annual report 2020.

Internationally, the FATF has already dealt with this form of money transfer in its 2013 report "The Role of Hawala and Other Similar Service Providers in Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing" and presented concrete typologies.

Quelle: FATF

Most of the typologies and cases mentioned by the FATF can also be implemented as rules in research systems for investigating transactions. They can lead to alerts in the systems that must be analysed by the obliged parties. Nevertheless, it seems useful to deal with the typologies and case studies more intensively in order to implement a sensible risk strategy.

Thus, not only in the context of hawala, but also in the context of terrorist financing, there is a recommendation to examine so-called "money collection accounts". The same applies to the case of "many to one", in which many different parties send money to one recipient. The sums are then immediately transferred abroad or withdrawn at ATMs.

When analysing such typologies, one can quickly come to the conclusion that hawala banking is a phenomenon that usually involves small sums of money.

This does not correspond to the facts. The whole issue is much more complex. We witnessed this in Germany in 2019 when the NRW State Criminal Police Office seized 26 million euros in cash from a precious metal dealer in Duisburg as part of a raid. It is assumed that this network alone has smuggled a total of 212 million euros over years, preferably to Turkey.

Quelle: Tageschau

Currently, we are confronted with a similar situation in the media. It shows the complexity of the system, but also that the German state is well aware of the risk.

Quelle: Radio MK

If you take a close look at the volume and the modus operandi, you will realise that none of the typologies published to date had even come close to grasping these cases.

The fact that this system, established over centuries, basically has a raison d'être in certain regions becomes clear by the example of foreign workers on the Arabian Peninsula. The workers there, preferably recruited from countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal or India, use the large number of HOSSPs (Hawala and Other Similar Service Providers) established there to transfer money at regular intervals to their families back home for their livelihoods. This system is of elementary importance in these countries, as often neither the principal nor the recipient have a bank account.

In Germany, the great challenge is to identify the providers of such services. Since new services, such as cash deposit machines, mean that contact with the customer is becoming less and less frequent and the number of personal contacts is also being reduced for cost reasons on the part of the obliged parties, an important element in the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism can no longer be actively practised: personal contact with the customer, which is still an elementary component of effective prevention.

Hawala banking will always remain part of the system in some regions of the world where the banking system is not as developed as in Europe. However, care must be taken that it is not abused by users to legalise incriminated values or to support terrorist activities.

Nevertheless, Hawala is not permitted in Germany due to the legislation. It requires enormous efforts on the part of law enforcement authorities as well as obliged parties to track down such complex payment procedures in order not to undermine the effectiveness of the prevention systems implemented in credit institutions.

On August 19, 2021, the Central Customs Authority published the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) Annual Report for the reporting year 2020, which aims to provide information on which economic sectors in Germany are particularly under the influence of (financial) criminal activities.

From the perspective of msg Rethink Compliance, the following topics play a special role in the annual report:

- Obligation of additional professional groups (DNFBPs - Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions)

- Trade-based money laundering

- Hawala banking

- COVID-19

- International cooperation

- Other observations

In our #rethinkcompliance blog, we will take a closer look at these topics in six parts. In today's blog, we first refer to the obligation of additional professional groups.

Obligation of Additional Professional Groups

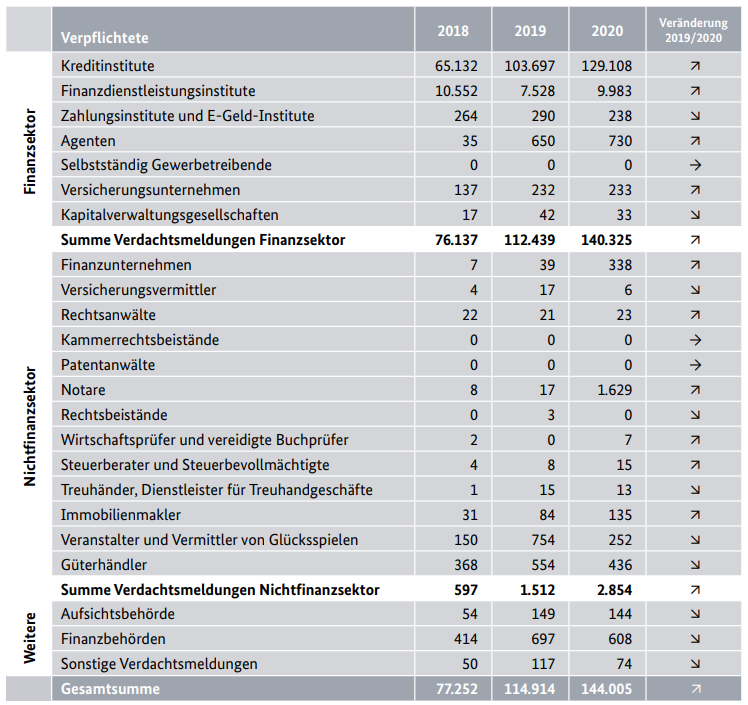

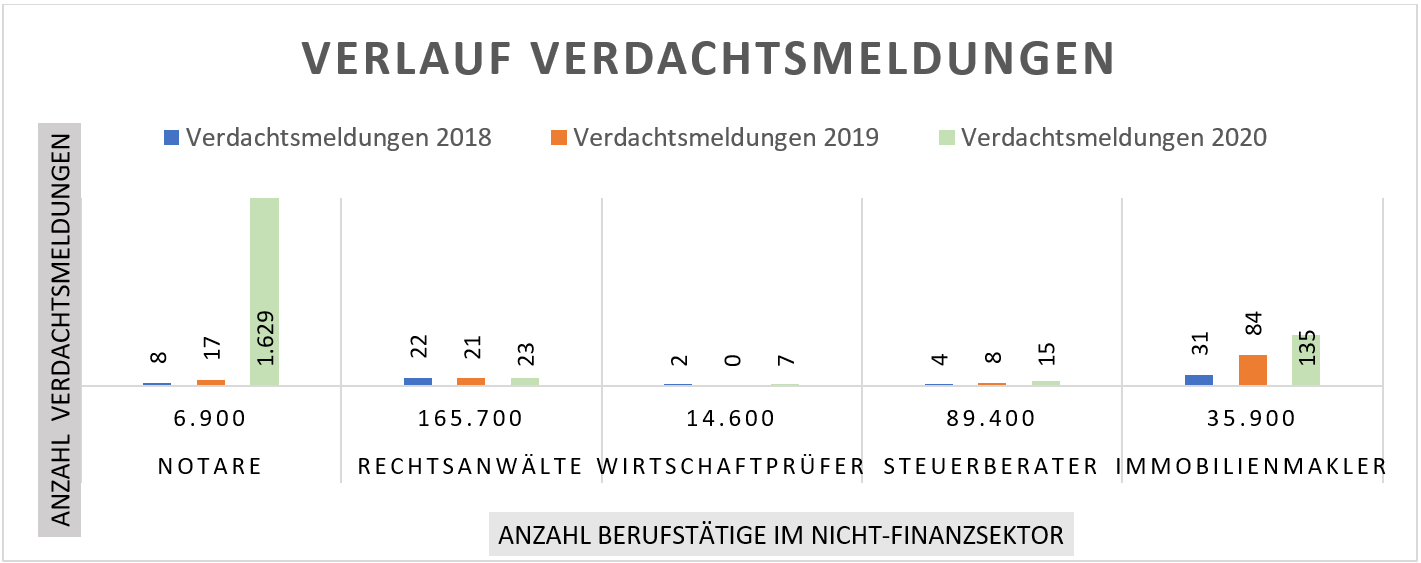

Following the first National Risk Analysis 2018/2019, which certified a high money laundering risk for the German real estate sector, the German Regulation GwGMeldV-Immobilien came into force on October 1, 2020. In addition to the real estate sector, it also obliges legal advisory professions, such as notaries, lawyers, auditors and tax consultants, to submit suspicious activity reports to the FIU.

As a consequence, it is not surprising that the number of suspicious activity reports from this circle has increased by leaps and bounds, especially among the professional group of notaries.

While there had been an increase of over 100% when comparing 2018 to 2019 (note: 8 SARs were submitted in 2018, and a total of 17 in 2019), there were a total of 1,629 reports to the FIU in 2020. It will therefore be interesting to observe whether this trend will continue in the following years and then remain at a high level.

Figure 1: Number of SARs by obligor group (Source: FIU Annual Report 2020)

The topic of money laundering is not entirely new for notaries. The Federal Ministry of Justice already drew attention to this in 2004. The publicly accessible study about the vulnerability of lawyers, tax consultants, notaries and auditors through money laundering („Gefährdung von Rechtsanwälten, Steuerberatern, Notaren und Wirtschaftsprüfern durch Geldwäsche“)

Source:

aimed at sensitising this professional group to the issue by means of specific cases. However, it first required a legal regulation to ensure that notaries also need to submit suspicious activity reports to the FIU from now on. For example, a report must be made if contracting parties come from risk countries or if the overall circumstances of the purchase price settlement do not appear conclusive. This is the case, among others, if there is a blatant disproportion between the purchase price and the known assets of the clients. With regards to the definition of a risk state, there is certainly still a need for clarification. To refer only to the list of the EU Delegated Regulation and to the list of countries published by the FATF seems to fall short. For example, the countries used by the so-called "Russian Laundromat" for its financial activities have not yet been recorded here.

It would be extremely helpful for those obliged under the German Money Laundering Act to know in which cases, for example, the professional group of notaries has submitted suspicious activity reports to the FIU. This should give obliged parties an indication of the typologies with which the banking industry must deal in connection with real estate financing. In the past, the FIU has done important preparatory work in this regard through its newsletters and the indications presented therein to inform obliged parties accordingly.

Overall, the obligation of notaries is a step in the right direction for more effective money laundering prevention. However, this comes very late. In the end, it remains to be said that the explosive increase in notifications appears to be justified and, according to the motto "better late than never", more than necessary.

It will continue to be important that this group of people is also randomly audited by independent bodies with regards to compliance with the legal regulation. The challenge for auditors will be to first create a catalog of indicators in order to be able to perform standardised audit procedures.

Following the experience of the notaries' offices, it will now also be interesting to see whether the case numbers of other obliged parties, such as real estate agents or tax consultants, will also show significant increases in the future.

Figure 2: Number of SARs by obliged party groups

We are looking forward to the FIU Annual Report 2021 to find out whether this trend will continue accordingly.

Contact

msg Rethink Compliance GmbH

Amelia-Mary-Earhart-Str. 14

60549 Frankfurt / Main

+49 69 580045-0

info@msg-compliance.com

msg group

msg Rethink Compliance is part of msg, an independent group of companies with more than 10,000 employees.

The msg group operates in 34 countries in the banking, insurance, automotive, consumer products, food, healthcare, life science & chemicals, public sector, telecommunications, manufacturing, travel & logistics and utilities industries. msg develops holistic software solutions and advises its customers on all aspects of information technology.