You'd like to find out more about the range of services offered by the msg group? Then visit the websites of msg and its group companies.

In April 2013, an outcry went through the media when over 1,000 people lost their lives in a building collapse of a textile factory in India. The affected workers had previously discovered cracks in the building but were forced to continue working. The question of who was to blame and who was responsible was in the air. Was it the supervisors who forced the workers to continue working despite the known defects in the building? Weren't the international fashion chains, which have their products manufactured as cheaply as possible, also partly to blame? Isn’t also the consumer to blame, for whom textiles cannot be cheap enough?

This tragedy of the loss of so many lives in the workplace was the impetus for a discussion about responsibility. Suddenly there was a worldwide discussion about fair working conditions in the textile industry. Even if this was not the birth of the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG), it at least accelerated efforts in this direction.

Six months after the disaster, there was an agreement called the "Rana Plaza Arrangement", whereby relatives received compensation. The companies initially refused, and it was not until October 2015 that the compensation was paid to those affected. Another change triggered by this event was the “Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh”. This stands for better protection and more safety in the textile factories in order to eliminate violations there. At the end of 2013, the minimum wage for textile workers was finally raised.[i]

What is covered by the Supply Chain Act?

In general, companies are aware of the risks of their operations in an international context. Nevertheless, they are often accused of producing cheaply abroad, for example, without taking care of the risks that arise for people and the environment. This is precisely where the LkSG comes into the picture. In the future, companies will bear responsibility for the violation of human and environmental rights along the supply chain.

The Supply Chain Act, which was passed on 11 June 2021, is intended to ensure that companies pay attention to human rights and the environment from the extraction of raw materials to the end customer. This applies both at home and abroad and is intended to prevent child labour, forced labour, discrimination and inadequate safety standards in the supply chain. Better working conditions should minimise the risk of occupational accidents and other health risks.

The term supply chain is broadly defined. According to section 2 V of the LkSG, this covers all products and services, in particular all steps at home and abroad that are necessary to manufacture the products and provide the services. In addition to its direct applicability, the indirect spillover effect of the LkSG should also be taken into account.

When must the contents of the new Supply Chain Act be implemented?

The LkSG will come into force on 1 January 2023. However, companies already have to adapt their risk management in accordance with the new legal requirement now. The Supply Chain Act obliges all companies to comply with a clear proportionate and reasonable legal framework to fulfil human rights due diligence obligations. The requirements are based on the due diligence standard.

Is my company affected by the LkSG?

The LkSG applies to all companies under German or foreign law, regardless of their legal form, if they have their main administrative or statutory seat or their headquarter in Germany.

In addition, companies that have a branch office in Germany pursuant to section 13 d of the HGB (German Trade Law) are also covered. German subsidiaries can also fall within the scope of the LkSG.

A further prerequisite is that the companies must have at least 3,000 employees, which also includes any employees sent abroad. In the case of parent companies, the number of employees of all companies belonging to the group must be included. The number of employees must also include temporary workers who have been working for the company for at least six months.

As of 1 January 2024, this threshold will drop from 3,000 to 1,000 employees.

Furthermore, in the summer of 2024, it is to be decided whether the scope of the LkSG will be extended even further, so that companies with less than 1,000 employees will also be obliged by the LkSG.

Experts suspect that companies that are not obliged parties under the LkSG will be at least indirectly affected. Companies working with them could contractually oblige them so that they too must comply with the due diligence requirements of the Supply Chain Act. Furthermore, supplying companies are indirectly affected by the LkSG.

What happens if I do not comply or comply too late with the new legal requirements?

If the LkSG is violated, fines of up to € 800,000 may be imposed for intentional and negligent violations. For companies with a turnover of more than € 400 million, the fine can be increased to up to two percent of the global turnover. Under section 22 of the LkSG, companies can even be excluded from public procurement for a period of up to three years if a fine of € 175,000 or more is imposed. A damaged image associated with a violation of the law could indirectly lead to further financial damage.

However, according to section 3 III of the LkSG, a civil liability of the company due to violations of due diligence obligations regarding the protection of human rights as well as the protection of the environment is excluded. Consequently, there is also no personal liability of the managing directors in the case of violations of the LkSG.

What are my obligations as a company?

The due diligence resulting from the LkSG can be divided as follows:

- own actions in one's own business area according to section 2 V no. 1, VI of the LkSG,

- the actions of a contractual partner,

- the actions of a direct supplier according to section 2 V no. 2, VII of the LkSG and

- the actions of an indirect supplier according to section 2 V no. 3, VIII of the LkSG.

This means that responsibility no longer ends exclusively within the company itself, but - as the name of the law suggests - extends beyond it: along the supply chain.

The Supply Chain Act contains a final catalogue of eleven internationally recognised human rights conventions. From the legal rights protected there, behavioural requirements or prohibitions for corporate action are derived in order to prevent a violation of protected legal positions. These include the prohibition of child labour, slavery and forced labour, the disregard of occupational health and safety, the withholding of an adequate wage, the disregard of the right to form trade unions or employee representatives, the denial of access to food and water as well as the unlawful deprivation of land and livelihoods.

In section 3 of the LkSG, the law only mentions the companies' obligation to make efforts. Therefore, there is neither a duty to succeed nor a warranty liability. Furthermore, all due diligence obligations are subject to an appropriateness proviso, which gives companies discretion and room for manoeuvre. A gradation of the duty results from the company’s existing possibilities of influence. As a result, according to section 3 III of the LkSG, companies cannot be held liable under civil law for a violation of the due diligence imposed on them. Thus, there is also no personal liability of the managing directors.

Even if companies have to observe human rights and environmental concerns, nothing impossible can be demanded of them. Due diligence obligations can be fulfilled even if the entire supply chain cannot be traced, or preventive or remedial measures cannot be taken in case these actions are practically or legally impossible.

Even though the LkSG has been criticised particularly by business associations because, according to them, it would harm competitiveness, for example, the topic of sustainability is not entirely new in the legal landscape. Since 2017, there has been an obligation under the CSR RUG (CSR Directive Implementation Act) to disclose certain sustainability aspects such as environmental and social concerns, employee concerns, respect for human rights and the fight against corruption.

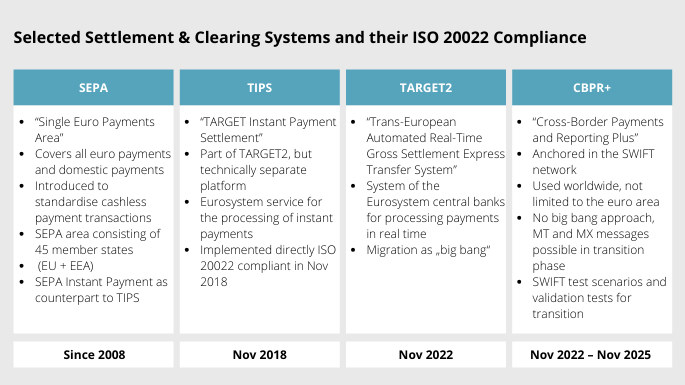

What compliance measures must be taken?

Based on the LkSG, companies and business managers are obliged to set up a compliance system to observe human rights and environmental due diligence obligations:

- Establishment of a corresponding risk management system

- Establishment of an internal responsible person or a representative

- Issuing a corresponding policy statement

- Implementation of a (direct/indirect event-based) supplier due diligence process

- Conducting regular/continuous risk analyses

- Focusing on risk-based and corrective actions

- Definition of preventive measures within the own business unit(s) and direct suppliers

- Establishment of a complaints procedure ("whistleblowing system")

- Documentation and reporting

The law stipulates in section 4 I of the LkSG that risk management must be established to identify, prevent, end or at least minimise risks and violations of human and environmental rights along their supply chains. The law indicates which preventive measures, obligations for complaint procedures and reporting are required for this. In addition, clear responsibilities must be established within the company to monitor the risk management system. A person responsible for risk management must be appointed within the company. According to section 5 of the LkSG, an appropriate risk analysis must be carried out to determine human rights and environmental risks.

At least once a year as well as on an ad hoc basis in the event of a significantly changed or expanded risk situation, the company must check its own business area and its direct suppliers whether there is a violation of human rights or environmental concerns. In the case of indirect suppliers, the obligation to conduct a risk analysis only exists if the company has sound knowledge of possible violations.

According to section 6 I and V of the LkSG, if companies identify a risk, they must immediately take appropriate preventive measures and review them annually and on an ad hoc basis. If the company then detects violations, it must take corrective measures. The last resort may also be the termination of the business relationship with the supplier.[ii]

Section 8 of the LkSG obliges companies to set up an appropriate internal complaints procedure. This is intended to enable individual persons to point out possible human rights or environmental risks and violations in the company's own business sector or at a direct supplier.

Pursuant to section 10 I of the LkSG, compliance with due diligence obligations shall be documented accordingly and kept for seven years. In addition, according to section 10 II to IV of the LkSG, there is an obligation to prepare an annual report on the fulfilment of due diligence obligations in the previous business year and to publish it on the company website no later than four months after the end of the business year. Furthermore, the management levels shall issue a policy statement for the human rights strategy of the company.

Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG)

The examination of ESG aspects plays a central role in the discussion of how companies position themselves in a way that is compliant with the LkSG. Against the background of a sustainable supply chain, the topics of environment, social (includes aspects such as safety, health of employees, labour rights, etc.) as well as corporate governance (includes topics such as corruption, etc.) must be taken into account. A rating of business partners for the entire spectrum of ESG areas should be included in the risk analysis in order to meet the requirements of legal due diligence.

Other regulations besides the LkSG

In addition to the German LkSG, there are other regulations that are to be taken into account in the international context:

EU Supply Chain Act: Since February 2020, there has been a draft for an EU Supply Chain Act. This goes much further than the German LkSG. The draft law is aimed at EU companies and companies operating in the EU with 500 or more employees and a turnover of more than € 150 million. According to the draft directive, the threshold is already 250 employees and € 40 million turnover in sectors that pose a risk to people and the environment.

The new EU regulation includes civil liability for companies. Affected parties can sue for damages in European courts. However, companies can be exempted from liability if they have set up a compliance management system that defends them. Even though it is only a draft at the moment, it makes sense to also orientate oneself on the EU regulations in the context of the implementation of the German LkSG in order to avoid having to make further costly improvements later on.

Bribery and corruption prevention: Within supply chain compliance, aspects of bribery and corruption prevention, which fall under governance in the ESG check, should also be taken into account. The fact that a large number of companies operate globally, foreign laws with extraterritorial application may also have to be taken into account.

US Foreign Corrupt Practice Act (FCPA): Originally, the FCPA only applied in the United States. It is considered the mother of all anti-corruption laws. In 1998, the FCPA was expanded to the effect that foreign companies and individuals could also be covered by the FCPA. A de facto effect has only been recorded since 2004 through increased implementation. This development has led to an enormous sensitivity to compliance issues worldwide and has set standards for the establishment of compliance management systems.

It consists of two parts:

- Anti-bribery rules: These prohibit giving or promising benefits to non-US public officials with corrupt intent to gain a business advantage.

- Accounting and internal control rules: These require proper accounting and data custody as well as internal control systems to ensure the proper use of company funds.

The FCPA has also encouraged other countries, such as Canada and the UK, to enact similar laws with extraterritorial application.

UK Bribery Act (UKBA): The law applies to all companies doing business in Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Neither the act of corruption nor the act intended by the bribery have to take place in the UK. As a result, any business with a foreign connection to the UK can be covered by this law.

German companies can be held accountable for corrupt behaviour anywhere in the world, even if the act of corruption is not related to an activity in the UK. It is sufficient that affected companies carry out business activities in the UK. However, the fact that shares of the company are traded on the London Stock Exchange or that subsidiaries are registered in the UK is not sufficient.

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC): The United Nations Global Compact has developed ten principles[iii] in the areas of human rights, labour standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption, which can be applied not only within one's own company but to the entire value chain. The UN Global Compact and the UN Global Compact Network Germany (UN GCD) call on companies to align their strategies with these ten principles. Even though it is a non-binding recommendation, the UNGC is the world's largest initiative for corporate sustainability (also known as corporate social responsibility) with 13,000 company participants and other stakeholders in over 170 countries. The guide "Sustainability in the Supply Chain[iv]" can be consulted by companies to help them establish and develop sustainable supply chain management. However, the UNGC looks at the relationship with upstream suppliers and does not focus on relationships with distributors, end customers or product disposal. The United Nations Global Compact Office will look more closely at actors downstream in the value chain in the future.[v]

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime offers a web-based anti-corruption portal called TRACK[vi] (Tools and Resources for Anti-Corruption Knowledge). “The UNCAC Legal Library is a comprehensive database of anti-corruption and asset recovery legislation and jurisprudence from over 175 States, systematized in accordance with the requirements of the Convention. The legal library, which will be regularly updated, identifies laws that have been successfully used to recover assets as well as barriers to asset recovery caused by inadequate or incompatible legal frameworks. This practical and user-friendly resource will aid countries as they design and improve their legal frameworks so that they are more conducive to the recovery of stolen assets.”[vii]

The database provides a unique overview of UNCAC articles and the corresponding provisions of national law. Searches can be limited to a specific country, UNCAC chapter and UNCAC article. Clicking on a country name opens a page with links to detailed information on domestic anti-corruption authorities and the full text of UNCAC-related laws. Here, too, companies can seek out targeted assistance and relevant information for their compliance.

Who checks compliance with the LkSG?

The Federal Office of Economics and Export Control checks compliance with the Act. It checks company reports and investigates complaints submitted.

An authority is provided with effective enforcement tools to monitor companies' supply chain management. The responsible authority, the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control, has far-reaching control powers. It can, for example, enter business premises, demand information and inspect documents, as well as request companies to take concrete action to fulfil their obligations and enforce this by imposing penalty payments.

Conclusion

The entry into force of the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act entails numerous legal obligations for companies. Not to be disregarded are the legal regulations from other countries, which must also be taken into account due to their extraterritorial effect. In addition, an ESG check is recommended.

Companies obliged under the LkSG must comply with a clear, proportionate and reasonable legal framework for due diligence. The requirements are based on the due diligence standard.

In addition to effective risk management, compliance with these legal obligations also requires more extensive duties and the implementation of various mechanisms that require a certain lead time. These cannot be named in general terms but must be clearly identified individually for each company.

In the download provided, you can make your own initial assessment of the type and scope of the legal obligations imposed by the LkSG that may affect your company. The following overview shows you which steps have to be taken to comply with the Supply Chain Act. If you have any further questions, please do not hesitate to contact us.

[i] Die Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen der Textilarbeiter in Indonesien. Welche Organisationen setzen sich für bessere Umstände ein?

[ii] Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz; NJW-Spezial 2021, 399

[iii] The Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact

[iv] UN Global Compact Office: NACHHALTIGKEIT IN DER LIEFERKETTE - Ein praktischer Leitfaden zur kontinuierlichen Verbesserung

[v] UN Global Compact Office: NACHHALTIGKEIT IN DER LIEFERKETTE - Ein praktischer Leitfaden zur kontinuierlichen Verbesserung

[vi] TRACK — UNODC's central platform of tools and resources for anti-corruption knowledge

[vii] UNCAC Legal Library Launched: New Database of Anti-Corruption Legislation from 178 States

On August 25, 2022 the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) published the final report ("Mutual Evaluation Report (MER)") on the audit of Germany. As a result, it should be noted that Germany has implemented considerable reforms over the past five years to better detect and combat money laundering activities and terrorism financing. These reforms are bearing fruits. However, further efforts are needed to optimize the effectiveness of prevention measures.

Poor domestic agency coordination and use of financial intelligence

The problems are not new but have long been known and discussed across agencies for many years. They include national coordination between the law enforcement agencies of the individual federal German states. While in the past the respective state criminal investigation offices sometimes conducted parallel investigations in an uncoordinated manner due to a lack of information flows, the creation of the financial intelligence unit (FIU) has already improved effectiveness in recent years. Nevertheless, the FATF has detected optimization potential here in the scope of its audits. It expects proactive risk prevention and improved availability and use of financial intelligence by the FIU. This includes, for example, access to bulk data and analytical tools to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the FIU analyses and to enable more intensive coordination and collaboration of FIU and law enforcement agencies. These findings need to be analyzed, not as a theoretical exercise but in cooperation with specialists and practitioners. Thereafter, implementation should take place as soon as possible, ideally with the involvement of the planned new German federal anti-money laundering authority.

Germany's cash intensity as a risk

In principle, the FATF has addressed cash intensity and unlicensed money transfer service providers as a particular risk. The fact that Germany is considered a cash-intensive country and that organized crime has taken advantage of this in the past to place incriminated money is not a new finding. Economic developments, especially the European interest rate policy, have led to a flight into tangible assets in recent years. The real estate sector is a case in point. One of the FATF's main criticisms is that real estate transactions in Germany can still be conducted in cash. For the banking industry, this means that there must be an even stronger focus on cash transactions than in the past. However, as a result of cost pressure and falling margins, institutions have increasingly switched to processing their services in connection with cash transactions via ATMs. Certainly, the regulation of the proof of origin for cash deposits above €10,000 has led to a sensitivity among obligated parties. However, the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin - Federal Supervisory Authority for Financial Services) communicated in its journal of August 2021 that the institutions can take into account the specifics of their respective business relationship in order to achieve a risk-oriented and practical procedure. This naturally leaves plenty of scope for design and interpretation for the banking industry. This leaves the obligated parties free to decide by which customers and in which form the proof of origin needs to be provided. Countries such as Spain, with an upper limit of €2,500, and Italy, with a maximum amount of €1,000, have already shown that such problems can also be addressed differently. Cash deposits above this amount are rejected in principle.

Problem area money value transfer services

Informal money value transfer services (see also MVTS in the #AML glossary) represent a particular problem area. While registered and established MVTS providers observe the legal requirements and are sensitized by the FIU to conspicuous facts or indicators, the informal MVTS are the focus of the FATF. Cases such as the large-scale raid by the North Rhine-Westphalian State Criminal Police Office (LKA NRW) on November 12, 2019, in which large amounts of cash and gold bars were seized from a jeweler’s in the Duisburg area, are seemingly just the tip of the iceberg. In total, more than 200 million euros were smuggled abroad without any name or sanction check. This way, the FATF addresses one of Germany's main problems: The prevention and control of Designated Non-Financial Business and Professions (see also DNFBPs in the #AML glossary) (FATF recommendations 18 and 23). The result of the audit of this group of obligated parties was one of the main points of criticism. It attested that Germany needs to make considerable efforts in a timely manner to meet the requirements of the FATF.

With this finding, Germany is in good company because countries such as Great Britain, Switzerland or the United States of America were attested as having the same deficit level. Even The Netherlands, which was highly praised on the day of the publication of the German report, is facing the same challenge. A first beneficial step would be to centralize the more than 300 supervisory authorities in Germany for this area. This should be accompanied by the establishment of uniform standards and appropriate, risk-oriented audits − similar to those which are known from the banking sector. Coordination with the above-stated countries would also be beneficial to achieve synergy effects and to define objectives and measures jointly, ideally in coordination with FATF.

Implementing asset recovery effectively

The topic of asset recovery was also addressed. The objective is to confiscate the illegally acquired asset values from the offenders. Germany evidences massive progress here. However, Germany still has a long way to go before it can match the effectiveness of other countries in this area. While in Germany the burden of proof still lies with the state, other countries have long since demonstrated how asset recovery can be implemented effectively. Even if there are initial moves in Germany to abolish the system of shifting the burden of proof, it remains to be seen to what extent such cases will be decided positively by the courts.

In Italy, defendants must prove that they are not involved in illegal business. There, a villa can be confiscated unless the owner can prove that it was purchased with legal funds. The situation is similar in Great Britain. British courts can force suspects to disclose the origin of their assets. They have the option of confiscating assets until the beneficial owner explains where the funds came from.

FIU problems

There has been considerable criticism of the effectiveness of the FIU, the anti-money laundering unit based at customs. This also comes as no real surprise because the media have already repeatedly and emphatically pointed out in recent years that there are obviously problems with the processing or follow-up of cases. Issues such as the pending suspicious activity reports (SAR) in the Wirecard scandal, the search of the FIU's premises due to investigations by the Osnabrück public prosecutor's office, and the large number of generally unprocessed cases at the FIU in the past have not been explicitly addressed. However, they lead to a negative perception among the population, the obligated parties and ultimately by the FATF. Despite all the scolding, the FIU must also be credited for its dependence on the information provided by the reporters and its quality. If the FIU receives SARs that are incomplete or contain incorrect data, the FIU's possibilities are limited, also in terms of international cooperation. You can find out which impact poor data quality can have on compliance in the #rethinkcompliance blog.

Challenges

That Germany is willing to meet the FATF's requirements is demonstrated by the paradigm shift anti-money laundering announced by Finance Minister Christian Lindner, including the creation of a new federal authority. However, this alone will not solve existing problems. It will require enormous efforts and cooperation with the different public authorities and sectors to make the work effective. This applies not only to the financial sector, but to a large extent also to the non-financial sector and DNFBPs already mentioned above.

Germany must report to the FATF within one year on the measures taken and progress made. Therefore, there is no time to wait for things to come. The BaFin, other obligated parties and the financial sector are facing major challenges in order to even begin to meet the FATF's expectations.

The Beginning of an End?

The fundamental concept of “foreign fighters” is not a modern-day innovation; historically, fighters from abroad have participated in several civil wars. A classic example is the International Brigades, a militant group constituted of foreign fighter volunteers from 50 different countries participating in Spanish Civil War. In the present time, however, the definition of foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) has gained in importance after its adoption in the Security Council Resolution 2170 (2014) following the Iraq crisis, which has been reaffirmed in the UNSC Res. 2396 (2017). A recently published joint report by Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) and Global Center on Cooperative Security attempted to explore the nuances of behavioural and financial profiles of FTFs in Southeast Asia by gathering and utilising financial intelligence by the Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) across this region to analyse and combat the catalytic effect of FTFs on terrorist activities.

The death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS in 2019, led to the immediate appointment of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi as the following leader of the Islamic State.[1] He was an ex-Iraqi army official, who had served Saddam Hussein, as well as a policymaker and was killed in a US raid in northern Syria earlier this year.[2] Also, he was placed on OFAC’s Specially Designated Global Terrorist list raising the question: Is this really the beginning of the end of violent terrorism perpetrated by one of the most powerful extremist organisations in modern history? Maybe not. Given the diminishing importance and influence of IS in recent years, several pro-ISIS offshoots are beginning to regroup with the hope to revive IS with any means available, including the recruitment of FTFs and the reception and utilisation of their returnees in their respective home countries. These offshoot organisations include multiple militant groups in Southeast Asia, such as Tawhid-wal Jihad, Katibah Nusantara (a group responsible for 2016 Jakarta Terrorist attacks), the Maute Group, FAKSI (a group from Java, Indonesisa pledging allegiance to ISIS) and many more. There already is a growing concern of FTFs being recruited via social media by several ISIS affiliates, sympathisers, and returnees from the Asian Pacific area.[3]

This article evaluates the threats posed by FTFs and the systems currently deployed to identify and assess the tactical and evasive methods used by foreign fighters.[4] Moreover, this article attempts to understand the movement, financial profile and transaction patterns and the potential red flags leading to the detection and prosecution. Finally, the article aims to serve as an additional source of knowledge on FTF profiling for compliance officers, anti-money laundering practitioners, and financial analysts in the counterterrorism landscape.

Who are the Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs)?

In order to respond effectively and efficiently to imminent re-emerging terrorist threats, it is imperative not only to identify the mechanisms of FTF transactional and behavioural patterns, the geographical emanation, transit and destination hubs as well as FTF returnees, but also to comprehend the FTF definition as described in the UNSC resolutions 1373 (2001), 2462 (2019), and 2178 (2014).

According to the UNSC resolution 2178,

“foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) are those individuals who travel or attempt to travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality, and other individuals who travel or attempt to travel from their territories to a State other than their States of residence or nationality, for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts, or the providing or receiving of terrorist training , including in connection with armed conflict.”[5]

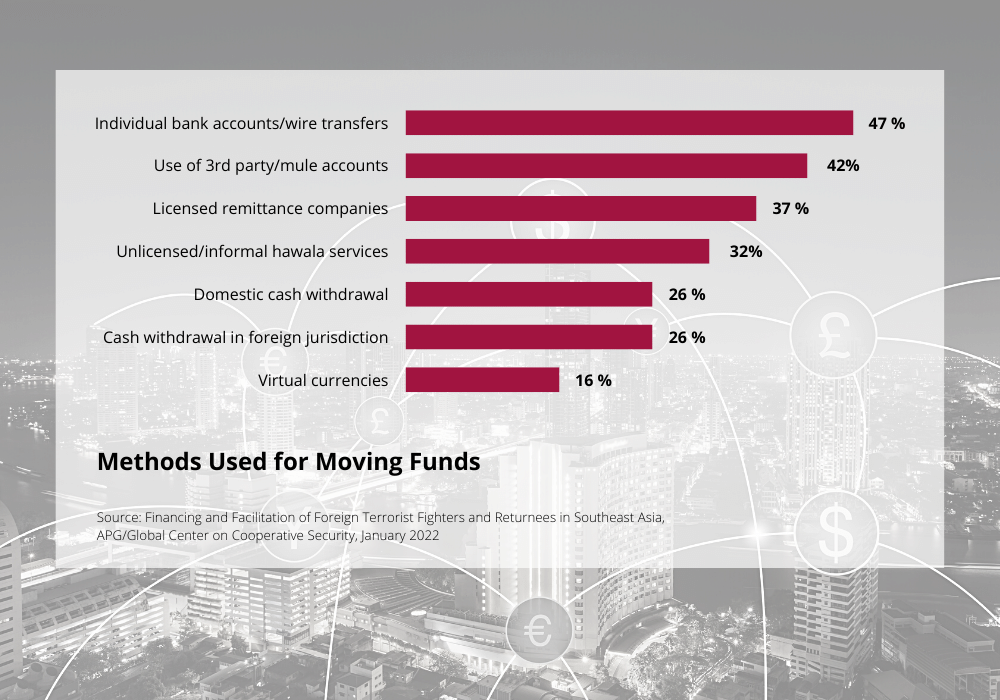

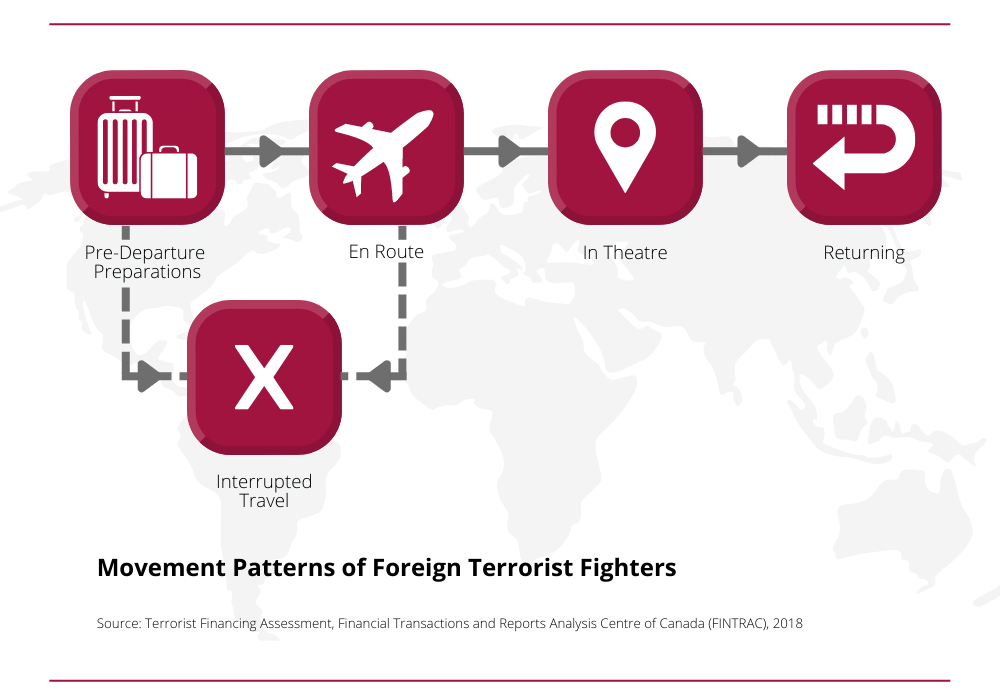

FTF planning, preparation and deployment require funds, so it is important to understand the geographical footprint and phases of FTF movements. This includes the point of origin, the transit routes and the various means of funding used to enable FTFs to carry out terrorist activities at the designated spots. Below snippet highlights commonly used methods for movement of funds involving FTFs.

Surveys of APG members including law enforcement and intelligence agencies have revealed that typically licensed and unlicensed remittance companies, wire transfers and cash withdrawals at home and abroad have been extensively utilised by the foreign fighters and their recruiting agents.

Re-Emergence & Drivers of FTF Activities

Part of the reason why ISIL offshoots are targeting Southeast Asia for recruitment is the influence of ISIS extremists on new militants, who view the group as the true bearer of the jihadi principles they have long upheld. Another factor for FTF re-emergence in the Southeast out of Daesh/ISIS is the affirmative influence of former members’ biased accounts on new militants, whose motivations are a complex mix of social, economic, cultural, ideological, and personal reasons. However, the following inexhaustive list sums up the main motivational factors for FTFs.[6]

- Religious narratives within the eschatologically oriented and misguided people willing to live under the rule of the so-called caliphate

- Ideological conviction

- Desire to improve the poor political and humanitarian conditions attributed to the atrocities of Syrian Civil War and oppressive dictatorship in Syria (typically a conflict-ridden zone in a broader sense)

- Sense of belonging, adventure, respect, opportunities for economic advancement, employment, marriage, and other material benefits

Following the territorial collapse of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant in particular, FTF recruitment focuses its attention on individuals and their families that are detained in camps, returning to their countries of origin, or travelling to a third country as well as on children of foreign fighters. However, several states have revoked FTFs’ citizenships to prevent their return, rendering them stateless.

Usage of Financial Intelligence against FTFs

In addition to a more generalised approach for the identification of red flag indicators aimed towards terrorist activities, more detailed information could benefit private sector actors in detecting and disrupting suspicious transactions related to FTFs or terrorist financing activities.

Example: Information about a very specific geographical area that is alleged to be a terrorist hotspot will enable reporting entities in the future to both better manage their risk of exposure to terrorist financing as well as to report more actionable and useful financial intelligence.

Below illustration shows a typical pattern of movement of foreign fighters which is subdivided into four to five stages.

Prior to Departure

- Pre-planned cessation of account activity by FTF

- Account statements indicating sale of personal possessions prior to date of travel

- Airline ticket purchases in proximity to conflict zones

- Account activity indicating funds received from social assistance, student loans, or other credit products

- Donations to NPOs linked to terrorist financing activities

- Use of funds for other travel-related items

En Route

- Irrational circuit of travel routes to the conflict zone with multiple means of travel

- Notice about a travel to a third country via a conflict zone but financial activities indicating an incomplete journey

- Financial activity alongside corridor to a conflict zone

- Receipt of wires inside or along the border of a conflict zone

In Theatre

- Inward money transfers from friends and relatives or terrorist accomplices

- Account goes dormant

- Media coverage on individual travellers to conflict zones

Return

- Dormant account suddenly becomes active

- Receiving new sources of income

- Atypical domestic or international fund transfers

Current Challenges

The categorisation as FTF depends on domestic legislation, which is guided by the international standard definition of whether the suspected individuals are “FTFs” or the groups they join are “designated terrorist groups”. This can cause inconsistencies in the application of FTF terminology, which is why it is imperative to adopt a globally accepted standard definition that makes a distinction between the terminologies of FTFs, general terrorists and the ones related to an armed conflict.

Additionally, the current red flag indicators for FTFs are rather broad and heavily biased toward the geographic location of the transactions associated with travel to a conflict zone or border region without the ability to determine whether they are legitimate or illegitimate. Lack of such information as well as the common profile of FTFs remain a practical challenge not only for the definition and identification of FTFs, but also for the analysis of their financial, behavioural, and geographic movement.

The usage of cash transactions between unknown, unrelated individuals and the transnational nature of FTF transactions constitute additional challenges. As customs and border officials are the first line of defence in the fight against FTFs, including them in the policy framework could be beneficial for an effective identification of FTFs and an appropriate reaction to FTF activities.

Another challenge is the lack of a robust feedback channel: Transactional relationships between law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and financial institutes (FIs) lack feedback on the quality and usefulness of information, which remains a bottleneck for investigating agencies in their collaborative efforts against foreign terrorists. Domestic communication from the financial and private sector and FIUs to law enforcement agencies is a one-way channel.[7] Feedback on a broad basis is important, not only in relation to specific cases. This is crucial to validate the correct flagging of information and how to improve reporting. This will help FIUs improve the refining of indicators, the quality and reliability of STRs as well as strategic and actionable intelligence.

Conclusion

While some APG members are continuously working on developing regulatory frameworks and strengthening their domestic AML CFT policies and procedures to prevent FTF activities and terrorism as a whole, other states have yet to establish (and, where already in place, reinforce) a well-defined AML framework to combat the financing of terrorism and intercept terrorist activities.

Governments also need to be mindful about the blurred lines of distinction between human rights violations, the categorisation of FTFs and armed conflicts versus a generalisation of terrorism. While several legal and compliance practitioners, FIUs and LEAs have investigated FTF related cases and developed a preliminary basis of red flags and indicators for the identification of FTFs, there still remain practical challenges to explicitly identify FTFs. At the moment, little data is available on incarcerated FTFs, as much of the information provided is unreliable and biased.

However, a combination of factors such as social and behavioural profiling of FTFs, geolocation and travel pattern analysis, understanding irrational account activity and a robust feedback communication between LEAs and FIUs will contribute to the preparedness against FTFs destabilising the region.

[1]Islamic State group names its new leader as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi - BBC News

[2]Islamic State leader Abu Ibrahim al-Qurayshi killed in Syria, US says - BBC News

[3]Southeast Asian Analysts: IS Steps Up Recruitment in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines

[4]Publication of Financing and Facilitation of FTFs and Returnees in Southeast Asia Report

[5]Investigation, Prosecution and Adjudication of Foreign Terrorist Fighter Cases for South and South-East Asia (unodc.org)

[6]Foreign Terrorist Fighters - Manual for Judicial Training Institutes South-Eastern Europe

[7]Publication of Financing and Facilitation of FTFs and Returnees in Southeast Asia Report

Contact

msg Rethink Compliance GmbH

Amelia-Mary-Earhart-Str. 14

60549 Frankfurt / Main

+49 69 580045-0

info@msg-compliance.com

msg group

msg Rethink Compliance is part of msg, an independent group of companies with more than 10,000 employees.

The msg group operates in 34 countries in the banking, insurance, automotive, consumer products, food, healthcare, life science & chemicals, public sector, telecommunications, manufacturing, travel & logistics and utilities industries. msg develops holistic software solutions and advises its customers on all aspects of information technology.