You'd like to find out more about the range of services offered by the msg group? Then visit the websites of msg and its group companies.

Why Your AML Segmentation Isn’t Enough

You're using an AML solution with rules and scenarios set up during the implementation project, generating alerts when transactions exceed certain thresholds. Maybe you've even segmented customers into broad categories like "corporate clients" and "private individuals" to fine-tune those thresholds.

Feels advanced, right?

Not quite.

Are all private individuals the same? Do all companies behave identically?

Spoiler: They don’t.

Setting thresholds based on broad categories alone is like using the same speed limit for bicycles and sports cars – it doesn’t make sense, and the regulator won’t favour this approach.

Our clustering approach for Siron®AML goes beyond these one-size-fits-all categories.

By analysing customer transaction behaviour, we uncover meaningful subgroups within each category. Think of it as introducing "sports car companies" and "bicycle companies" instead of just "companies".

We use advanced statistical methods: first, we identify the correlation dimensions, then compute a suitable number of clusters. There’s no AI involved, so everything is explainable – even to the auditor.

With this refined segmentation, you can:

- Set more precise thresholds

- Reduce false positives (fewer pointless alerts!)

- Improve detection of truly suspicious activity

The next step: Backtesting

Once the new subcategories are defined, the logical next step is backtesting. We help you fine-tune thresholds for these newly identified groups, ensuring your AML system is not only compliant but also efficient.

Want to stop drowning in irrelevant alerts and start catching the real risks?

In this blog post, I would like to provide an outlook on 2023 and the following years, this means the near future of our domain that is dedicated to fighting financial crime. As always with such outlooks, this one does not claim to be complete, but is a mixture of subjective perception and observation and objective analysis.

As there are different perspectives on the area of “Anti-Financial Crime Compliance”, I would like to start by outlining what is meant by this, without going into too many details. This is followed by an assessment of 2022 and an outlook for the near future. At msg Rethink Compliance, we summarize the following areas under the term “Anti-Financial Crime” (AFC). Each of these areas is to be regarded individually even if there are overlaps between them. For this, see our Glossary.

- AML/CFT Compliance. The acronym stands for anti-money laundering (AML) and identification of terrorism financing (Combating the Financing of Terrorism), sometimes abbreviated as CTF (Counter-Terrorist Financing).

- KYC Compliance. This acronym stands for Know Your Customer (KYC), although we define it a bit broader and interpret “C” it as “Counter party”, commonly meaning the business partner, whether the business partner is a supplier, a development partner, sponsoring partner, sales agent or customer.

- ABC Compliance. In our context, this is a common acronym for fighting corruption and bribery (Anti-Bribery & Corruption).

- Fraud Prevention. Interestingly, there seems to be no comprehensive acronym for the English term fraud prevention. However, only could derive FPD from Fraud Prevention & Detection.

- ESG Compliance. Implicitly, ESG compliance consists of KYC, ABC and fraud prevention. As this is not clear to everyone, I list this topic, which also includes the block Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), individually here.

- Sanctions. The area of finance embargo monitoring, which itself is already covered by the areas AML/CFT and KYC, will also be listed here individually.

Explicitly excluded from this consideration are the areas of tax evasion, which overlaps with AML and KYC, and the area of anti-cybercrime, which in a broader sense is part of fraud prevention but which is an individual topic in the area of industrial espionage, for example. We take this into account in the msg group and offer specialist expertise in the form of msg security advisors.

For 2022, the Financial Crimes News platform provides what I consider to be a very good and structured overview and analysis of events, including interesting questions (Fighting Financial Crime in 2022 – Dashboard by FCN). Since almost every software vendor in the field never tires of commenting on the events of the year, sometimes more, sometimes less, I don't want to join the ranks.

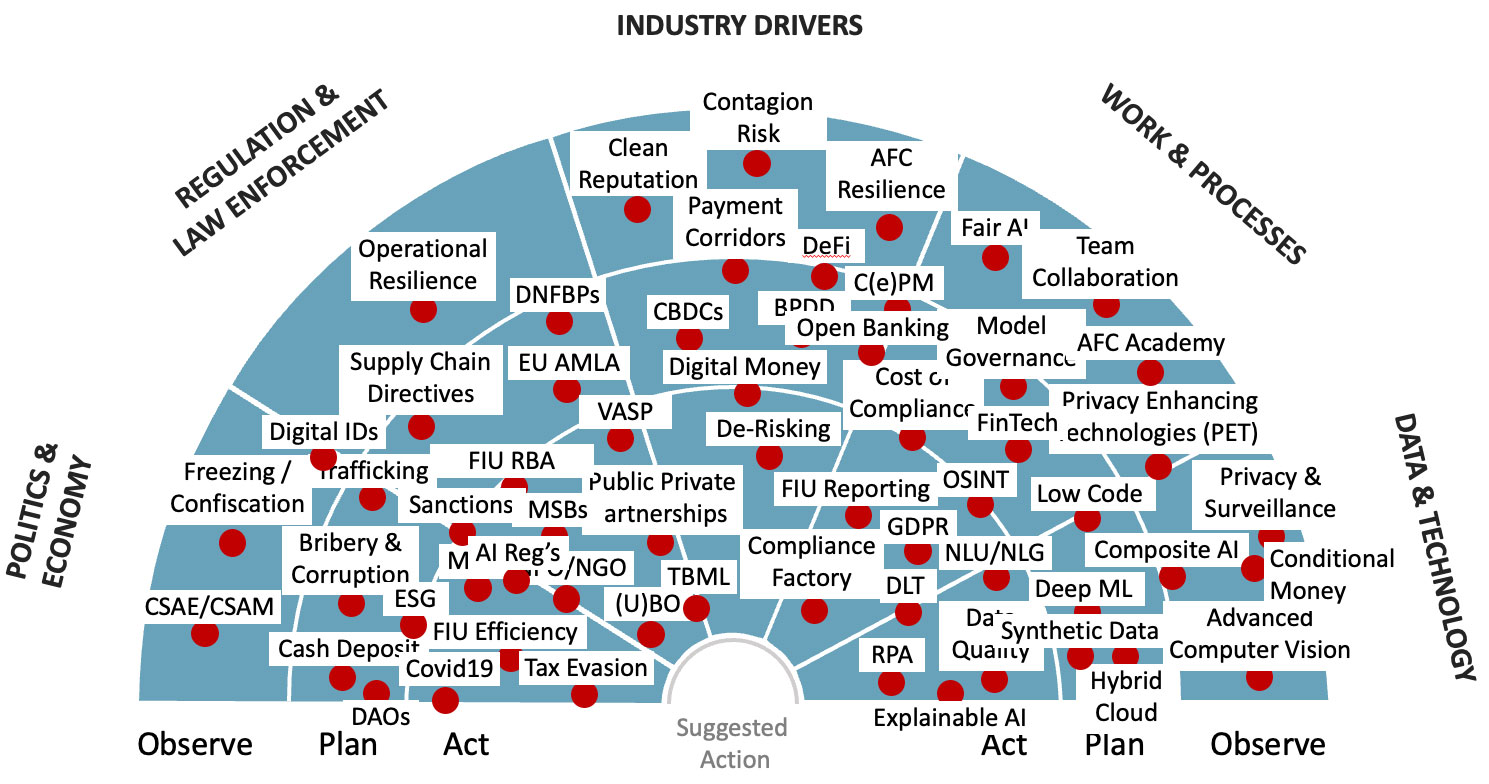

We are continuously and systematically investigating the market. For this, we have developed our AFC Radar, in which we take a closer look at all stakeholders, collect observations, identify trends, and then examine the extent to which these have significant impact on AFC compliance. This includes politicians, regulators, watchdog organizations or the affected industries such as banking, insurance and others. But we also consider changes in the type of work, availability of technologies, system suppliers and software providers as well as the possible uses of the applications. We attempt to corroborate these observations using four consideration perspectives. The following illustration gives a rough impression of the multitude of drivers considered.

Basically, we can assume that these drivers are motivated by a general desire to improve the fight against white-collar crime. Following a recent discussion about artificial Intelligence (AI), I recently tried ChatGPT, an advanced chatbot prototype from the US-based OpenAI. I asked “Got any ideas to improve combating financial crime?” and received the following answer from the AI-driven bot[i]:

- Improved recognition and monitoring systems: Using advanced analytics and machine learning, financial institutions can more effectively detect and monitor suspicious activities.

- Improved collaboration and information sharing: Financial institutions can collaborate and share information about potential finance crimes, which will help better detect and prevent these crimes.

- Increased regulatory oversight: A stronger regulation framework and a stricter enforcement of regulations can help deter financial crimes by increasing the risk of detection and punishment.

- Better education and awareness: Educating the public about financial crimes and how to protect themselves may reduce the number of victims of these crimes.

- Improved international cooperation: Financial crime often crosses national borders, making international cooperation essential to effectively combat it. This can include sharing information and coordinating enforcement efforts.

- Using technologies: The use of blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies can help increase transparency and traceability of financial transactions, making it harder for criminals to operate.

The underlying transformer-based machine learning model[ii] has been trained using a large dataset of conversations. Mainstream dominates here, not necessarily facts. Thus, these six points mentioned by ChatGPT hardly come as a surprise. This remains the case if one further questions each individual aspect of the above answers. Even on the question of how this can be implemented, the model provides clues. We have already pointed out the particular importance of transformer models, including the newer feedback transformer architectures[iii], for regulatory compliance at various conferences, as well as the problems, especially with respect to perception bias of AI/ML. ChatGPT has attracted a great deal of attention and received much acclaim. However, there are wholly different questions critical to this specific artificial intelligence that we will not pursue here now. Nevertheless, one can predict that in the area of AFC compliance, the use of technology - which ultimately includes AI/ML - will continue to grow to increase effectiveness and efficiency.

For the near future of AFC compliance, we also see the following additional topics, signals and trends, among others:

Regulation & Supervision. Under this heading I have tried to present our main observations on the requirements and behaviors of regulators and supervisory authorities, without going into new laws or adaptations of existing laws (AMLA (Anti-Money Laundering Act), LkSG (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz), EU Supply Chain Directive, EU AI Act and many more). I have also left out specific industry topics such as Target2 in payment transactions, which is to be successfully implemented in the EU this year, the real estate sector, which is facing tighter regulation and supervision, DNFBPs (“Designated Non-Financial Businesses & Professions”) which will see similar challenges or the challenges in payments and eCommerce. Instead, I will deal with the generally applicable topics below.

- Policy & Control Management. Preventing ethical misconduct of employees without having to introduce additional rules and controls and taking into account that human beings do not necessarily act rationally in all situations, demands a risk management approach that works on a behavior basis (“Behavioral Risk Management”). This can be used to trigger so-called "nudges", i.e., thought-provoking and reminder devices, to help employees behave within the framework of the rules and specifications. This is another approach to prevention that can prevent problems from arising in the first place. There is already initial experience of implementation in this area, although there are as yet no best practices.

- Compliance Resilience. Resilience in this context follows Markus Brunnermeier's concept of resilient societies.[iv] This states that it is not only about resilience but about flexible adaptability to new conditions in such a way that societies are not permanently damaged in the long term. We are seeing an increased focus among international regulators, but also increasingly within the EU, to demand such resilience and also to review it. This goes hand in hand with a significantly reduced response time for obligated parties. Backtesting, stress testing and ad-hoc simulations of the monitoring and screening solutions used, as well as the adequacy of the risk analyses, represent the major challenges here.

- Risk Assessment & Analysis. The aforementioned regulatory requirements for companies to become more resilient and agile, also with regard to compliance, leads to a clear emphasis on the regulatory risk model and thus the areas of risk assessment and risk analysis. Let me put it this way: While an annual look at compliance risk assessment has been sufficient in the past, this will no longer be the case in the foreseeable future. While we don't see an indication to address the topic on a weekly basis, we do see an indication to address it on a quarterly, if not monthly basis, not to mention ad-hoc requests. This will force compliance departments into a different form of implementation planning and control, which has long been standard in other areas and is very closely linked to the area of “Enterprise Performance Management”. In the near future, however, this will be more of a free skate. However, backtesting, which in some countries and regions has so far been treated more as a marginal issue in regulatory compliance, will become mandatory. What justifies exactly those thresholds, exactly those ratios, and exactly those chosen exclusion criteria? Officers have better answers to these questions and can point to a systematic approach. Also part of this topic block are ownership analyses of legal entities in order to identify the beneficial owner(s) in compliance with the law. Here, we participated in the FATF consultations on Recommendation 24 in 2022. The uncoordinated and patchy implementation of transparency registers within the EU and the lack of governance on the part of the authorities mean that this topic will continue to be a focus and challenge for officers in 2023 and the near future. There is currently no improvement in sight. Please see our blog post for more information. [👉 Selina Trotno & Natalie Hürler: From a Backup Register to a Full Register – Are the Alterations by the German Act TraFinG Enough?] However, there are more and more market intermediaries offering solutions usually with a regional focus (for example, Russia and Ukraine or Africa) for qualitative automation. This is also an area where the use of technology will continue to grow rapidly in line with the tightened sanctions regimes. New challenges are also emerging from the field of ESG ("Environment, Social, Governance"), which are spilling over into institution or company-specific risk models and risk analyses from various regulations.

- Public-Private Partnerships & Private-Private Partnerships. In our opinion, both will receive attention in the future and will be necessary to improve the situation in the fight against incriminated funds. However, it needs to start with the public-public partnerships. One would think that the Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) of this world would find it easy to share data in such a way that concrete starting points for law enforcement and prevention can be efficiently derived from it. There are many reasons why this can only be agreed to a limited extent. One major reason is different data protection regulations and, of course, different politically motivated systems. Since the latter will be difficult to influence, in the area of data protection, reference should be made to technological progress that simplifies exchange using so-called "privacy enhancing technologies," or PET for short. I would also like to refer you to our blog post on this topic. [👉Natalie Hürler: Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) in the Fight Against Financial Crime]. This is also an approach for the other form of partnerships. Purely private-sector partnerships are seldom seen as an effective means of improving the fight against white-collar crime. The fear of rejection by the supervisory authority and the fear of data protection problems are too great here. But how is KYC compliance to be ensured and made more effective in the future without exorbitantly increasing costs and/or the associated risks? In our opinion, this is only possible through cross-company exchange and cooperation.

In the area of industry drivers, I would like to mention the following from the sum of the identified observations:

- Metaverse & Web3. The first steps into metaverse for bank and financial services providers and even more so for consumer brands have been taken. Not much else has happened so far, despite billions in investment, although the gamer metaverse is clearly on the rise with Roblox and Fortnite. The sober balance of the metaverse may also be due to the swelling dispute over how identities can be established and protected, who owns what data, and what regulation can/will be used and how. Web3 is based on the idea that ownership of data is shared between creators and users, thus avoiding domination by large corporations. It is supposed to be the decentralized continuation of Web2, i.e., the Internet as we know and experience it today. That’s the theory. In fact, a complete digital economy is to be created. The first ATMs in the metaverse already exist, and the payment service providers are getting ready. Nevertheless, we still see the coming months here as more of a playground for advertising and marketing. Considering that it took 15-20 years for the Internet to hit the banking world, but only 5-6 years for app-based mobile banking, we may assume that it will at least not take longer with the metaverse, especially considering that most areas of smart cities will also need Web3 as a basis. The closer you are already to cryptocurrencies, NFTs and smart contracts with your business model, the faster the metaverse and Web3 will gain relevance, also in the AFC environment.

- Smart Contracts & NFTs. Let’s start with the simpler one, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). These unique proofs of ownership are a core component of the Web3 but are already well advanced in their broad adaptation. Apart from their existence in digital art, trading and tokenization represent interesting features that suggest NFTs will continue to grow in the near future. Similar to the metaverse, the consumer goods industry is leading the way here. We should therefore not just reduce NFTs to an asset class but perceive them as an interesting technology. This is even more true for smart contracts. These are digital contracts in the form of an application based on blockchain technology. These smart contracts can act through their own application when certain conditions are met and do not require human supervision. The parties to the contract are defined by tokens. The first financial products based on smart contracts are emerging to facilitate trade finance. Smart contracts are also increasingly being used in the supply chains of commercial and industrial companies. In the future, we expect to see more complex trading constructs that are subject to volatility and therefore also require smart adjustments to these self-executing contracts. But the extent to which this helps combat trade-related money laundering depends on the acceptance and increasing adaptation of the technology.

- Crypto Currencies. Away from being viewed as a speculative asset rather than a substitute for fiat currencies, this asset class will continue to endure. Whether you call the crypto winter a structural collapse or a controlled crash, it will not change the fact that crypto currencies are here to stay. From the perspective of AFC compliance, they are a risky asset. It is imperative that this be reflected in the risk model and risk analysis, and it will leave many anti-money laundering officers with question marks. After the collapse of the trading platform FTX and now alleged transparency issues at Binance, crypto exchanges are facing an increased regulatory attention. In these cases, however, it is more in terms of unraveling potential fraud scenarios, specifically in the area of financial reporting. Either way, crypto exchanges are in for at least one more frosty spring in the coming months after the crypto winter.

Effectiveness & Efficiency. We are inclined to always think of this point as technologically motivated. But that’s not true. Although the topics of automation and AI/ML play a major role in the discussion in this area, it would be fatal to assume that technology alone can bring about an improvement in the situation. Technology – whether new or changed – should always entail an adaptation of processes and, if necessary, of the organizational structure, or this should even precede the technology.

- Compliance Resilience addresses the effectiveness perspective and represents an increasing challenge for obligated parties. To manage this efficiently, concepts are needed. Technologies and techniques are available. We will present such a concept in the scope of our AFC Governance initiative soon. We see this as a long-term focus for obligated parties, system providers and integrators in the coming years.

- Technology Use. In the same corner, I would see the increasing use of automation techniques as well as AI adoption. In addition to the further use of robotic process automation (RPA), the topic of entity resolution (ER) should also be mentioned, which will increasingly contribute to an improvement in quality and thus to an automation of decisions in the area of KYC processes. With regard to AI, reference should be made to the bunq ruling[v], which will certainly result in further AI adaptation in regulatory compliance. In our opinion, little will change in the use cases. These are known and should be implemented in a well-considered manner – taking into account the application guidelines of the regulators, but also the specific regulation (keywords here are EU AI Act or New York AI Bias Act, among other things). AI is a supplement and not necessarily a replacement of existing rule-based systems. Again, our research into the vendor landscape (AML/KYC application providers) shows increasing openness, ranging from existing interfaces to AI models to embedding these models. Cooperation and coexistence instead of competition and substitution, in other words. However, the area of explainable AI would have to be mentioned here as a key technology in the case of a (partial) replacement of rule-based systems. Due to the fact that there is hardly reliable training data − not to mention fuzzy FIU reports and their underlying data − it is all the more important to recognize model biases and understand how results are found. In addition, mention should be made of "digital twins" for handling peaks in case processing as well as the area of "Natural Language Processing" (see the above mentioned ChatGPT) for case disposition and/or pre-assessment of raised cases. As AI/ML become more prevalent in the AFC space, the issues of operations and reliable and efficient deployment ("Machine Learning Operations" (MLOps)) will become more important.

- Data Integration, Data Quality & Data Protection. Data quality is an idle topic that is at least as old as my professional career to date. On the one hand, some regulators, including Bafin, have called for measures to be taken to improve data quality where necessary. On the other hand, the quality of the data is of much higher importance when working with AI/ML methods. In this respect, there are two motivations in AFC compliance for taking action, however unwelcome the topic may be. An evaluation of the corresponding application notes of Bafin on this point can be found here: 👉Mirko Janyga: Item 6 of the AuA BT - BaFin Concretizations on Monitoring Systems helpful, 👉Uwe Weber: Impact of Poor Data Quality on Compliance. Data integration is part of data quality, but it poses its own challenges in digital transformation, especially in the traditional banking environment, including AFC. This is less true for neo banks due to the lack of IT system history. That the topic is strategically relevant has been known for some time. Whether it will be addressed in the current economic environment remains questionable. The issue of data protection is also not a new one. But in the context of the public-public, public-private and private-private partnerships mentioned above, it will inevitably be a pressing issue for FIUs, officers, and also industrial companies in compliance in 2023 and subsequent years. I would also like to mention synthesization of data related to the AI/ML technologies mentioned above, which is very beneficial for backtesting. Especially the latter will be of great importance this year, as described above in the area of regulation, for model governance, the monitoring of risk models.

- Total Cost of Ownership. With all the IT initiatives, the multitude of systems, system components and high integration points in the area of AFC, the costs of AFC compliance are also becoming a focus of attention in the current economic situation. Besides the standardization of systems, the homogenization of the system landscape and the improved integration of data, the question is increasingly being asked whether a simple reduction to a one-vendor strategy is not just as problematic as the other extreme, the best-in-class strategy. The discussion is rounded off by outsourcing on the one hand and insourcing on the other. Both are also driven by one or the other regulation, for example AMLA. In addition to the actual software systems, the operating models are also put to the test in AFC compliance.

One could write a lot more, but in my opinion the points listed above represent a good mix of currently discussed challenges and those to be expected in the near future. Unsurprisingly, AFC compliance remains a challenging topic in 2023, both in terms of effectiveness and the need to improve efficiency and proportionality of resources.

[i] ChatGPT Dec 15 Version in a Free Research Preview; Original Question: “Got any ideas to improve combating financial crime?”

[ii] Transformer refers to a deep learning model based on sequential data input, but which can be parallelized, helping to significantly reduce training time.

[iii] The term “Feedback Transformer” originates from a research paper dated January 25, 2021 by the authors Angela Fan, Thibaut Lavril, Edouard Grave, Armand Joulin and Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, all from Facebook AI Research, in which the limitations of traditional transformer models were identified as well as the possible elimination of these restrictions. We tend to find the term misleading and usually use the term “recursive transformer”. Here, all layers in a vector are fed into the model memory per time step, not just the representations of the lower levels.. This results in much more powerful models.

[iv] Compare Brunnermeier, M. K. (2021), The Resilient Society, 2nd Edition.

[v] On October 18, 2022, the competent court in Amsterdam ruled that Neobank bunq could very well use artificial intelligence methods to combat money laundering. Among other things, this has so far been rejected by the Dutch central bank. However, the ruling also confirms shortcomings of the bank in the effectiveness of monitoring, especially in the area of customer risk classification. Both DNB and bunq see their opinions confirmed in the ruling. With regard to the use of modern technology to combat money laundering, DNB has announced on the basis of the ruling that it will enter into a dialog with the financial sector

Much is being written about and reported on the topic of supply chain compliance, whether this be the German Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz (LkSG/Supply Chain Act), the corresponding EU directive that is in preparation, or the extraterritorial laws that have been valid internationally for some time and also affect the supply chain such as the UK Bribery Act (UKBA) or the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). My colleagues have already addressed the content of the individual guidelines as well as the broader context on bribery, corruption and ESG and have published this in other blog posts. [👉Pinar Karacinar-Gehweiler: Compliance Requirements Due to the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act; 👉Lea Ilina: ESG in the Tension Field of Corruption]. This blog post now outlines a corresponding IT system to support supply chain compliance and shows which components should be part of such a system, how and why.

Even if the above-mentioned regulations seem to have little in common at first glance, they all have at least the following points in common:

- Risk Analysis: The basis for compliance with the regulations is the creation of a company-specific risk analysis covering, among other things, vendors, their relationship to your own company, regions, products and services, contract types and other risk objects. It seems beneficial to initially create this risk analysis for all regulations, if this has not already been done, or to expand the existing risk analysis accordingly.

- Vendor Screening: The most obvious part of a supply chain compliance system is the "Know Your Customer" (KYC) screening of vendors. This part is referred to differently on the market: KYV (“Know Your Vendor“), KYBP (“Know Your Business Partner“), etc. We like to translate the "C" as Counterpart and can get by with the KYC principle without any problems. Apart from the confusion of terms, the point here is to know the business partner per se and the relevant actors of the partner, if any, and to check against relevant lists. In addition to sanctions lists, PEP lists (PEP = Politically Exposed Persons) and other information such as negative news ("Adverse Media") must also be used. Here, three levels need to be considered: Identity screening, integrity screening, and specific risk screening against the risks identified in the risk analysis. This screening takes place initially when the request/decision is made as to whether a business relationship can/may/should be entered into, as well as on an ongoing and risk-based basis.

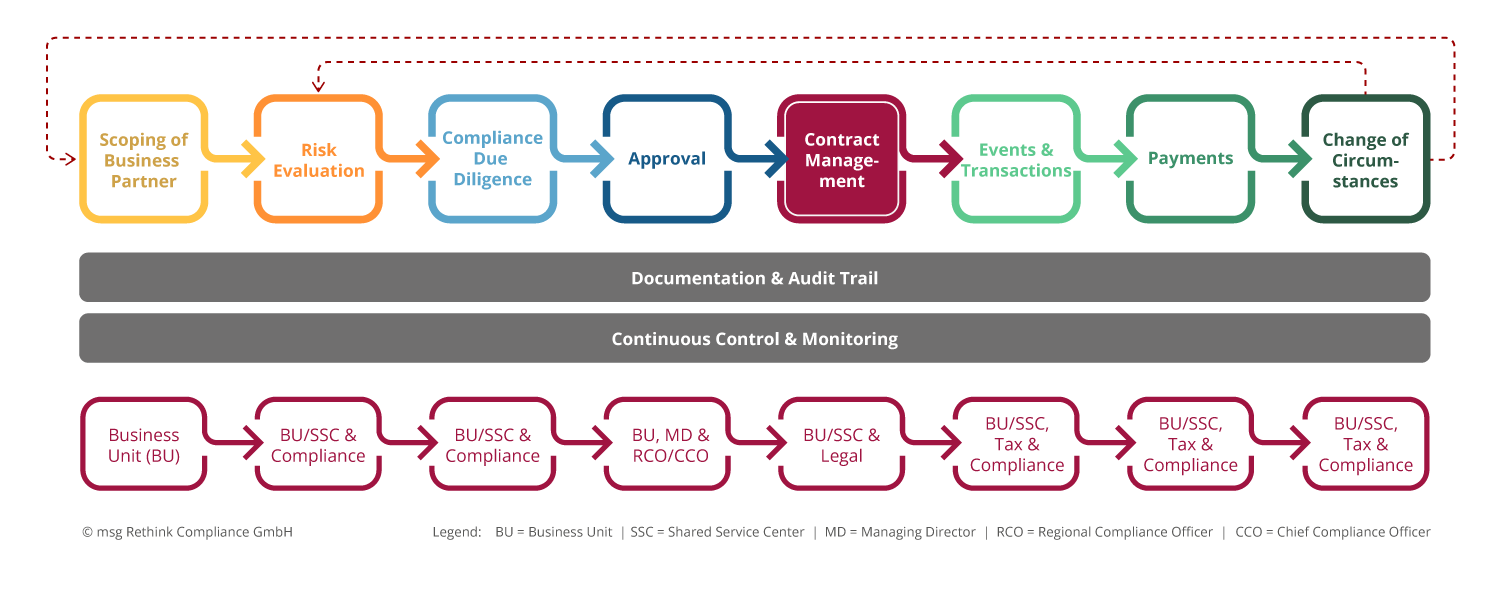

This results in the following process view on the topic:

Fig. 1: Process view business partner screening

Combining the topics outlined above enables efficiency and productivity benefits to be leveraged. This makes it possible to create a uniform system for business partner compliance that covers and presents the relevant company-specific risks in a holistic manner. In addition to transparency benefits, this results above all in the avoidance of redundancy in processing both within the company and on the part of the business partner, i.e. the vendor. The support provided by a flexible IT system, called a supply chain compliance solution for simplicity’s sake, further contributes to cost reduction by avoiding IT silos, redundant data preparation and storage, and reducing other direct and indirect costs of such a software solution compared to multiple stand-alone solutions.

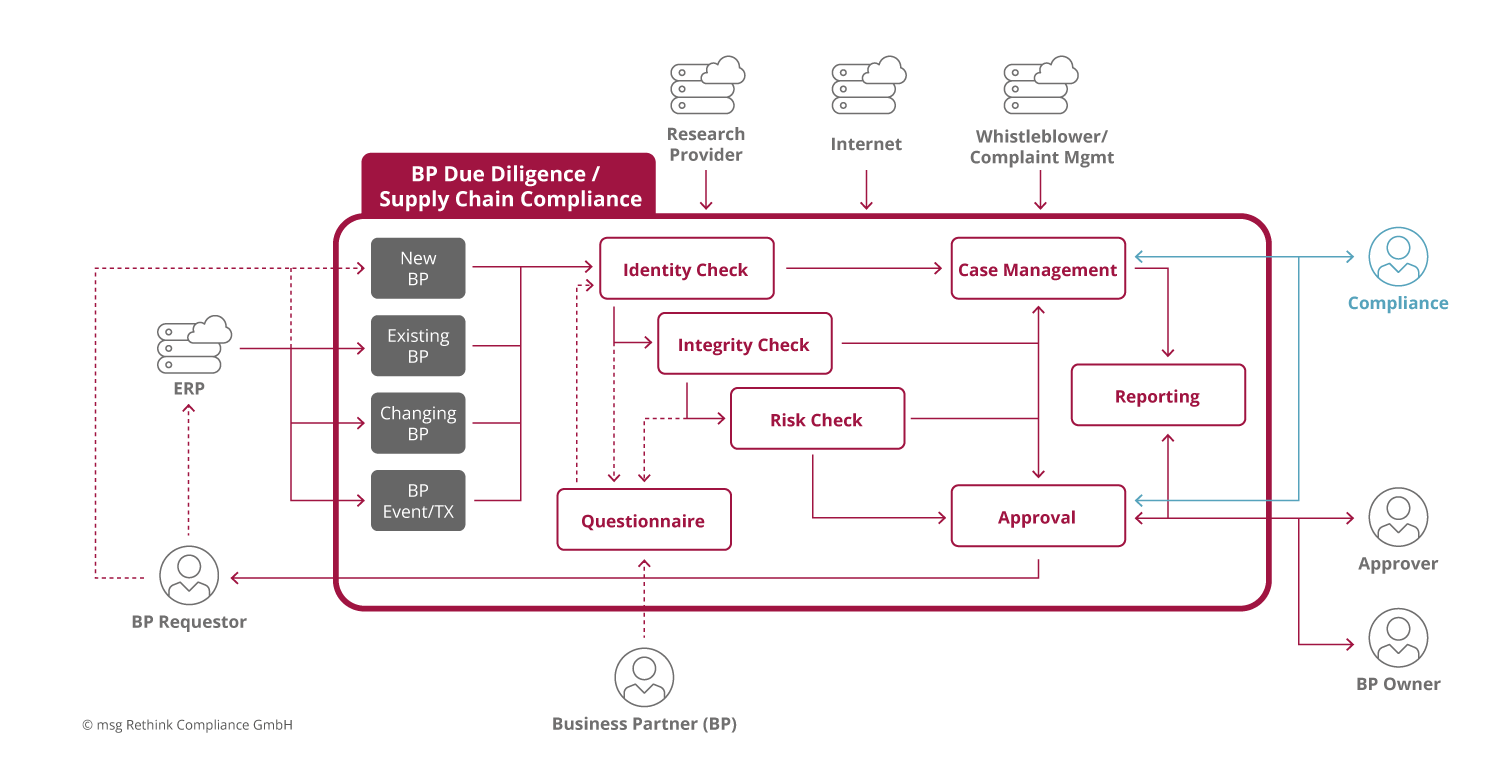

Based on the above considerations in connection with the process-related view of a business partner lifecycle, the following schematic structure results for the construction of such a flexible software solution, starting with the core processes:

- Identity Check (Check of business partner master data): In addition to the legal name and address, for example members of the governing bodies (managing directors, advisory boards, executive boards, etc.) and ownership structure (keyword: beneficial owner) need to be recorded. This information plays an important role in the automatic further processing for various reasons. This check needs to be conducted during the on-boarding process but also for continuous monitoring. As the process name suggests, this involves establishing the identity of the business partner in all its aspects. Connections to credit agencies and intermediaries, such as Dun & Bradstreet or similar, can increase the level of automation. The use of flexible, dynamic, digital questionnaires can also have a positive impact on efficiency. They help reduce redundancies and can be used as a self-service component in the bidding process, for example.

- Integrity Check (Check of identified master data of business partners against a number of lists (direct as well as indirect/sectoral sanctions, PEP, companies with bad press/unfriendly media, etc.)): This list set is different from the one used for identity check. Typically, compliance-specific lists are used here. Of course, in the area of sanctions management, it is also possible to work with the publicly provided lists of the EU, USA, UK and, for example, the World Bank. However, in the context of a make-or-buy consideration, both the expense and the risks of data management must be taken into account. In addition to the check during onboarding of a business partner, integrity must also be checked continuously, as the associated risk can change constantly.

- Specific Risk Check: To check the extended data of business partners for relationship risks with regard to regulatory aspects (non-operational risks), rules derived from the risk analysis are defined, which can then give rise to so-called "red flags", i.e. risk-relevant facts that need to be assessed and processed. It is advisable to perform this check during the onboarding of the business partner and to review it periodically on the basis of the risk rating after the decision to enter into a business relationship has been made. It is also advisable to be able to design the risk model flexibly. On the one hand, this means the possibility of defining additional checking rules as required - preferably by the relevant department - and, on the other hand, of making changes to the risk scoring model. A risk scoring model with dominant risks has proven to be both effective and efficient here. The digital questionnaire component already mentioned has also proven advantageous in the past, as long as it can be flexible in its structure and dynamically interactive in its responses.

- Event & Transaction Check: The event and transaction check can be implemented at different levels of complexity. In addition to some standard checks for high-risk transactions, it is also possible, for example, to work here on the basis of a fraud prevention system already in use. Even though this is not recommended, this area is often given lower priority in a software-based solution. This has not least to do with the complexity of the matter in connection with the implemented process reality in companies and in their ERP systems. This check is therefore often outsourced transaction-specifically per company directive to the so-called "first line of defense" (operational controls) and "third line of defense" (internal audit) as well as whistleblower systems and supported secondarily by means of IT. However, artificial intelligence and process mining functionalities offer new, highly efficient IT support and automation options that can significantly reduce the risk of bribery and corruption in this area.

- Case Management: All alerts and generated cases from identity, integrity and risk checks must be analyzed and decided, if necessary only after an extended check, also called "enhanced due diligence" (EDD). A case management system makes all of this transparent, enables the necessary processing quality to be ensured, and enables the complexity-controlled distribution or delegation of leads, cases or partial aspects thereof. Typically, the software solution generates a proposal for the initial risk to be confirmed or rejected based on the previous testing steps. This, in turn, defines that the risk should ideally be subdivided as follows:

- Initial risk, which is initially identified and confirmed during onboarding.

- Ongoing risk that continuously arises and changes as a result of collaboration (primarily through risk-relevant master data changes or corresponding events and transactions).

- Manual risk, which is manually controlled by an appropriately authorized employee.

- Inherited risk, which exists, for example, due to company affiliation or beneficial owners. In contrast to the aforementioned three, this type of risk is optional in connection with business partner compliance.

- Approval Management: The acceptance of a specific risk position of a specific business partner must be approved by the company's decision-makers in close cooperation with Compliance. In most cases, Compliance acts only as an advisor; in other cases, it should demand a right of decision or veto. This is done as part of the approval management process. In connection with the risk model mentioned above, an identified gross risk resulting from the risk analysis can thus be mitigated by measures related to the business relationship and the associated contract administration - if this is allowed. In such a case, the result is then the net risk on which a decision would have to be made. It goes without saying that all measures must be logged as part of the approval process in order to ensure auditability. The process-related illustration above shows that this does not only apply to approval management, but runs through the entire process.

- Reporting: In addition to audit reports, this includes the regulatory requirements for management reports, which should be supported from within the application on a template basis so as to save time and effort. Reporting for management on the risk situation along the supply chain and governance across the entire business partner process should also be mentioned in this context.

After the core processes have been roughly described, the question arises of the actors who must work on or with such a system, in other words, the question of interfaces and user roles. Here, too, the list is shown schematically.

Interfaces:

- ERP System(s): This primarily refers to the system in which the master data is managed. This can be an ERP system, or it can be a CRM, SCM, MDM, bidding portal, or similar system that manages business partner master data, events, and transactions (e.g., Microsoft, Salesforce, SAP, and others). It is not uncommon to have multiple systems. The type of integration determines the degree of automation and the acceptance of the system in the overall process.

- Credit Agencies/Research Providers: These are public or licensed providers of relevant content on business partners that can/should be used for master data maintenance as well as for risk assessment (e.g., Dow Jones, Dun & Bradstreet, Moody's, but also public lists of the EU, UK, USA, etc.). Here, from a risk perspective, it is necessary to define which providers and data sources should be worked with. For example, there are special providers who specialize in business partners from certain regions, e.g., the former CIS states or the Arabic-speaking world, as well as generalists. Depending on the risk appetite, one provider can be chosen for the simple risk check, and another for the extended risk check or quality assurance

- Internet: For a deeper online research on a specific business partner, an Internet search that can be logged should be provided.

- Whistleblower/Complaint Management: The possibility to lodge a complaint about direct/indirect business partners must be set up and covered, e.g. according to LkSG. An investigation and risk reassessment must then be performed. This can be implemented as an interface to an existing system or by means of a company directive and manual recording of a corresponding note as part of the core process for case management.

With regard to the interfaces, it should be noted that this does not address specific, country- or industry-specific reporting requirements to regulators, which may be another interface requirement.

User roles:

- BP Requestor: This role requests a new business partner/vendor and/or a new business partner relationship.

- BP Owner: This role "owns" and is responsible for a specific business partner and/or business partner relationship.

- Compliance: This role is only intended as an example of Compliance as a user role. This role can be sub-divided as required.

- Approver: This role exemplifies the business decision makers who can review and approve/deny the addition of a specific business partner and/or change the risk potential of an existing business partner.

- Business Partner: The business partner or vendor can be directly involved in the process as part of a self-service.

With regard to the roles, it should be noted that these must always be set up on a company-specific basis and that these, as well as the role designations, may well be different.

This roughly results in the following use case diagram for an IT-supported supply chain compliance system:

Fig. 2: Use case diagram of an IT-based system for supply chain compliance (without event/transaction monitoring).

The outlined IT-supported implementation of a business partner compliance system is generic and, in this form, can support the regulatory compliance requirements for cooperation with business partners in general (sales partners, joint ventures, research initiatives, HR partners, etc.) and vendors in particular. Regulatory specifics have been omitted for clarity, as have industry-specific requirements. As part of this blog series, we will soon also provide insights and examples on risk model, audit strategy and reporting. So it's worth following the #rethinkcompliance blog and staying tuned.

Contact

msg Rethink Compliance GmbH

Amelia-Mary-Earhart-Str. 14

60549 Frankfurt / Main

+49 69 580045-0

info@msg-compliance.com

msg group

msg Rethink Compliance is part of msg, an independent group of companies with more than 10,000 employees.

The msg group operates in 34 countries in the banking, insurance, automotive, consumer products, food, healthcare, life science & chemicals, public sector, telecommunications, manufacturing, travel & logistics and utilities industries. msg develops holistic software solutions and advises its customers on all aspects of information technology.